Hello, friends! Welcome back to the A to Z Challenge. For this year’s challenge, my theme is the planet Mercury, and in today’s post F is for:

FIVE

Today’s post is really an important life lesson: you can’t always trust your own eyes. Your eyes will play tricks on you, and they may cause you to make some pretty embarrassing mistakes. Back in the late 1800’s, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli’s eyes played a trick on him, causing him to miscalculate Mercury’s rotation rate.

We touched on this briefly in a previous post. Based on telescopic observations of Mercury, Schiaparelli determined that Mercury has a rotation rate of approximately 88 Earth days. This matches nicely with Mercury’s orbital period, which is also about 88 Earth days long. If Schiaparelli’s calculations were correct, this would mean that Mercury is tidally locked to the Sun. The same thing happened to Earth’s Moon. The Moon’s rotation rate and orbital period are both approximately 27 Earth days long, which is why the same side of the Moon always faces toward the Earth.

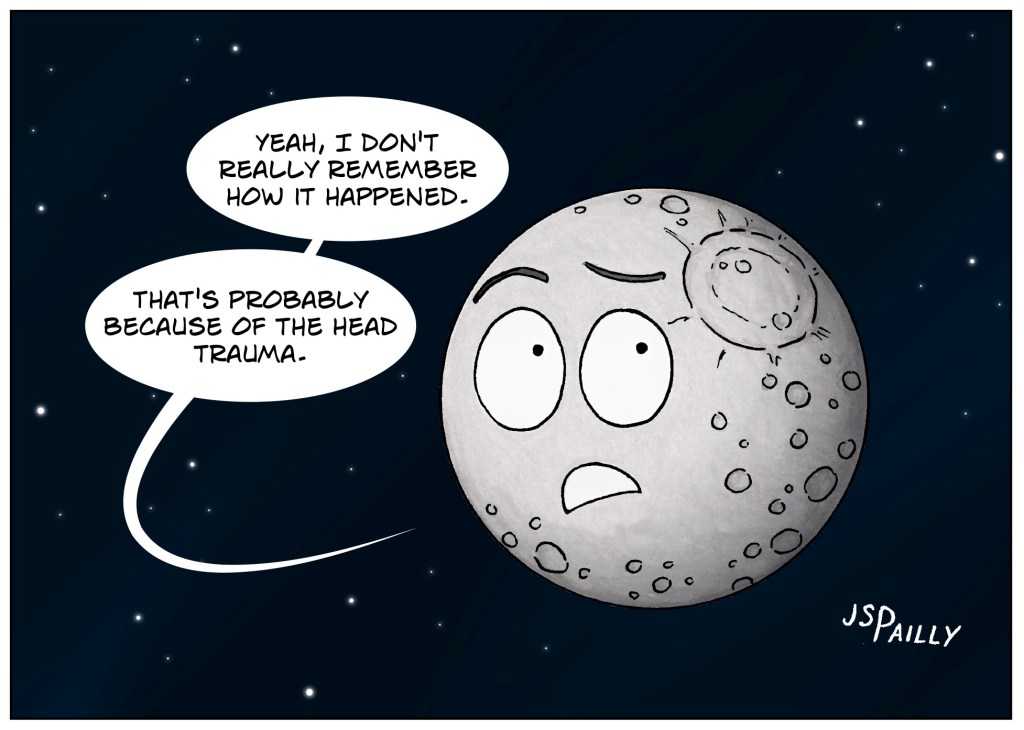

But Schiaparelli’s calculations were not correct. We now know that Mercury’s true rotation rate is about 59 Earth days, not 88. So how did Schiaparelli, an otherwise highly competent and highly accomplished astronomer, get this so wrong? It’s because when he started his observing campaign of Mercury, he noticed a pattern of splotches on Mercury’s surface that kind of looked like the number five. And as he continued his observations, he kept seeing this splotchy five shape on Mercury’s surface.

The thing is, if you stare long enough and hard enough at the surface of Mercury, you can probably find the number five in several different places. I’d normally include one of my own drawings here, but in this case I think you really need to see an actual map of Mercury.

A bit of confirmation bias was probably at work. After seeing a five on Mercury the first few times he looked, Schiaparelli had an expectation. He expected to see the five again, and every time he did find a five on Mercury, Schiaparelli assumed it was the same five. To make matters worse, Schiaparelli also thought he could see clouds on Mercury, so whenever he saw only part of a five, he could easily deceive himself into assuming the rest of the five must be hidden under cloud cover.

As a result, Schiaparelli calculated Mercury’s rotation rate based on faulty observations, and he got a result that triggered a second case of confirmation bias. Just as the Moon is very close to the Earth, Mercury is very close to the Sun, so it made sense—it fit well with Schiaparelli’s expectations—that Mercury rotation rate would match its orbital period. It made sense, in Schiaparelli’s mind, for Mercury to be tidally locked to the Sun.

To be fair to Schiaparelli, another astronomer had previously tried to calculate Mercury’s rotation rate and gotten an answer of 24 hours (the same as Earth’s rotation rate). So while Schiaparelli was wrong, he was, at least, less wrong than the last guy. And that’s often the way science advances. Science isn’t always right, but it keeps becoming less and less wrong than it was before.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Here’s an article from Astronomy.com about Schiaparelli’s five, and some of the other shapes he thought he saw on Mercury’s surface.

And regarding that point I made at the end, about science being less and less wrong than it was before, here’s a famous article by Isaac Asimov called “The Relativity of Wrong.” It’s a must read for anyone who has even a passing interest in how science works.