Hello, friends! For this year’s A to Z Challenge, I’ll be telling you a little about my upcoming Sci-Fi adventure series, Tomorrow News Network. In today’s post, A is for:

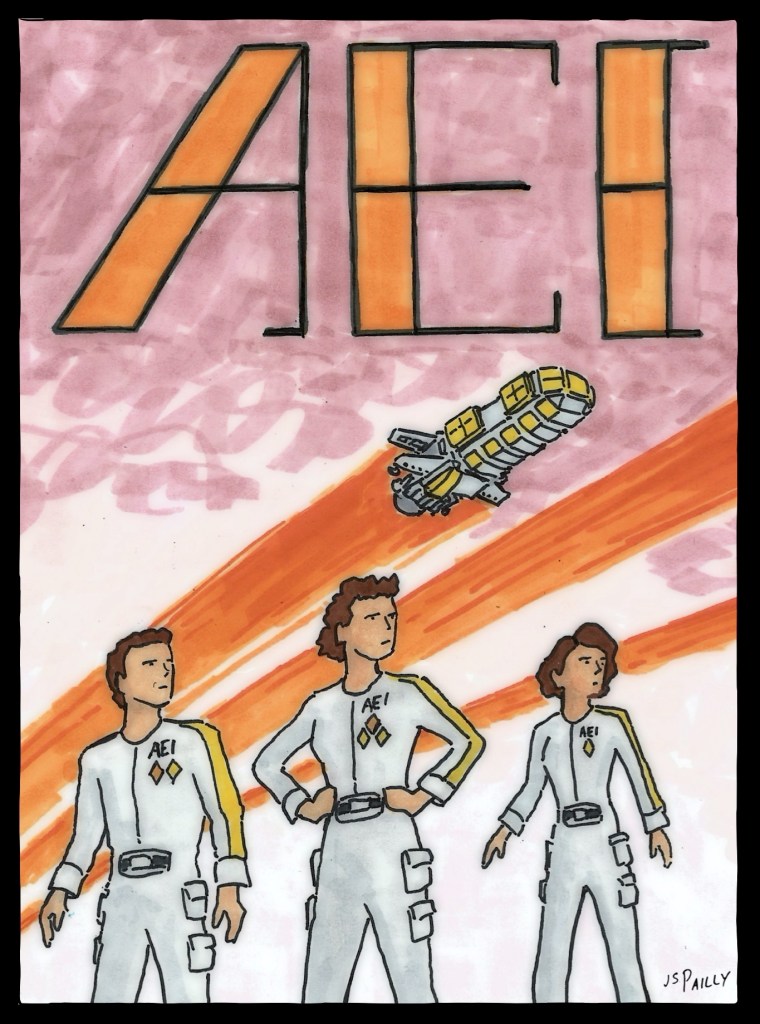

ALKALI EXTRACTION INCORPORATED (A.E.I.)

Faceless mega-corporations are everywhere in science fiction. We see them in the Alien movies. We see them in RoboCop, we see them in Blade Runner. So when I started writing the first story in my Tomorrow News Network series, including a faceless mega-corporation just felt right.

In early drafts, I wanted to say as little about this faceless mega-corporation as possible. I didn’t even give it a name. The good people of Litho Colony all work for “the Company,” and whenever somebody mentioned “the Company,” everyone else would know which company they were talking about. There was no need to be more specific.

My thought was that the Company was so big and so faceless that it didn’t need a name. My critique group disagreed. I got a lot of feedback from people asking who this giant corporate entity was. What did they do? What products or services did they sell? And thus Alkali Extraction Incorporated (better known as A.E.I.) was born.

A.E.I. is a mining company specializing in the mining of rare chemical resources from planets along the galactic frontier. They’re one of the leading suppliers of lithium for the Earth Empire, and they’ve recently expanded into the market for mesotronic elements—chemical elements that are stuck in a quantum state between matter and antimatter.

Litho Colony is the property of A.E.I. The colonists do sometimes refer to A.E.I. as “the Company,” but they also sometimes refer to the Company by its actual name. How could they not? The letters “A.E.I.” are stamped everywhere, a constant reminder to the colonists of who their employers are.

Looking back on those early drafts of Tomorrow News Newtwork, book one, I get what I was trying to do with my faceless and also nameless mega-corporation. But my critique group was right, and I’m glad I listened to them.

Next time on Tomorrow News Network: A to Z, the planet Berzelius has five moons. Wait, let me count again. Sorry, the planet Berzelius has six moons.