Today’s post is part of a special series here on Planet Pailly called Sciency Words. Every Friday, we take a look at a new and interesting scientific term to help us all expand our scientific vocabularies together. Today’s word is:

SILICOSIS

What’s the scariest thing about the Moon? Moondust.

- First, moondust gets all over your spacesuit. During the Apollo missions, astronauts found it was practically impossible to get all the dust off their spaceboots and spacesuits, possibly due to a sort of static cling effect. So astronauts wound up tracking a lot of this stuff back into the lunar lander.

- Next, it gets in your air supply. Once all that moondust got into the lander, the Moon’s low gravity meant dust particles could drift about in the air a lot longer than they would on Earth—just waiting for someone to breathe them in.

- Finally, it gets in your lungs. Roughly half of moondust is composed of fine grains of silicon dioxide. Essentially, moondust has the consistency of powdered glass. You don’t want that in your lungs.

On Earth, the inhalation of silica dust can cause a respiratory disease called silicosis. Symptoms include coughing, shortness of breath, and swelling or inflammation of the lungs. Those most at risk include miners and quarry workers, as well as anyone working in the glass manufacturing industry.

At least one astronaut reported experiencing silicosis-like symptoms while on the Moon. Future Moon missions and possible lunar settlements will likely involve longer-term exposure and higher risks of respiratory diseases.

So while this may sound like an odd piece of advise, given that the Moon is airless, please be careful about the air you breathe on the Moon.

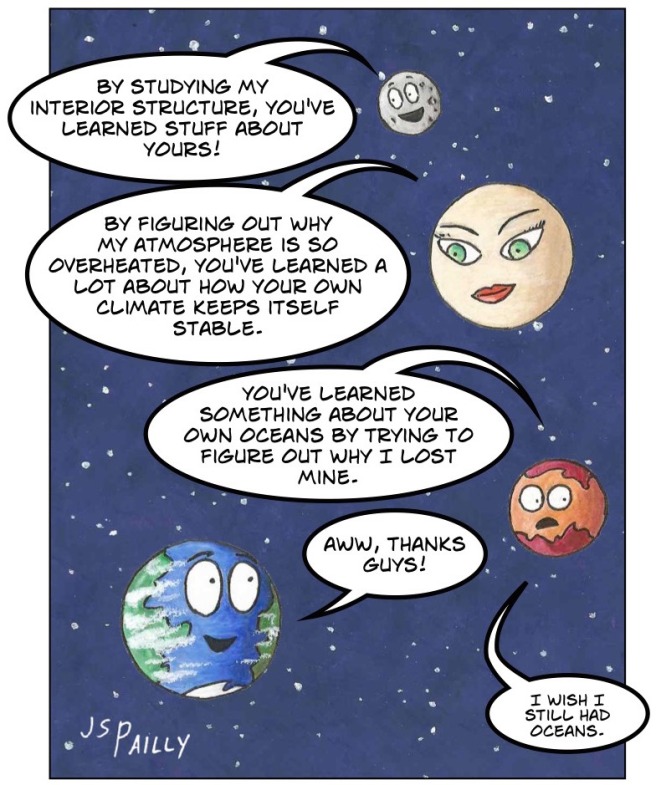

P.S.: Silicosis or similar respiratory conditions will also be problematic for Mars missions. The surface of Mars is covered in iron oxide dust (a.k.a. rust). I for one don’t want to breathe in flecks of rust any more than I want to inhale powdered glass. Martian soil may also contain other as-yet-unidentified chemicals that could be hazardous to human health.

Links

Silicosis from MedLine Plus.

Don’t Breathe the Moondust from NASA Science.

The Mysterious Smell of Moondust from NASA Science.

Occupational Health: Lunar Lung Disease from Environmental Health Perspectives.

* * *

Today’s post is part of Moon month for the 2015 Mission to the Solar System. Click here for more about this series.