Hello, friends! We are halfway through this year’s A to Z Challenge. I have to admit when I picked the planet Mercury as my theme for this year’s challenge, I was a little worried I wouldn’t be able to find enough material for a full alphabet worth of posts. But Mercury has not disappointed me. There are more than enough Mercury facts to cover! In today’s post, N is for:

NASA MISSIONS TO MERCURY

Which planet is closest to the Sun? More often than not, the answer is probably Mercury. That may seem counterintuitive, since the orbital path of Venus (the 2nd planet) lies between the orbital paths of Mercury (the 1st planet) and Earth (the 3rd planet). But consider it this way: every time Venus and Earth happen to be on opposite sides of the Sun, Mercury is somewhere in between. So on average, Mercury ends up being the closest planet to Earth more often than Venus, Mars, or any other planet.

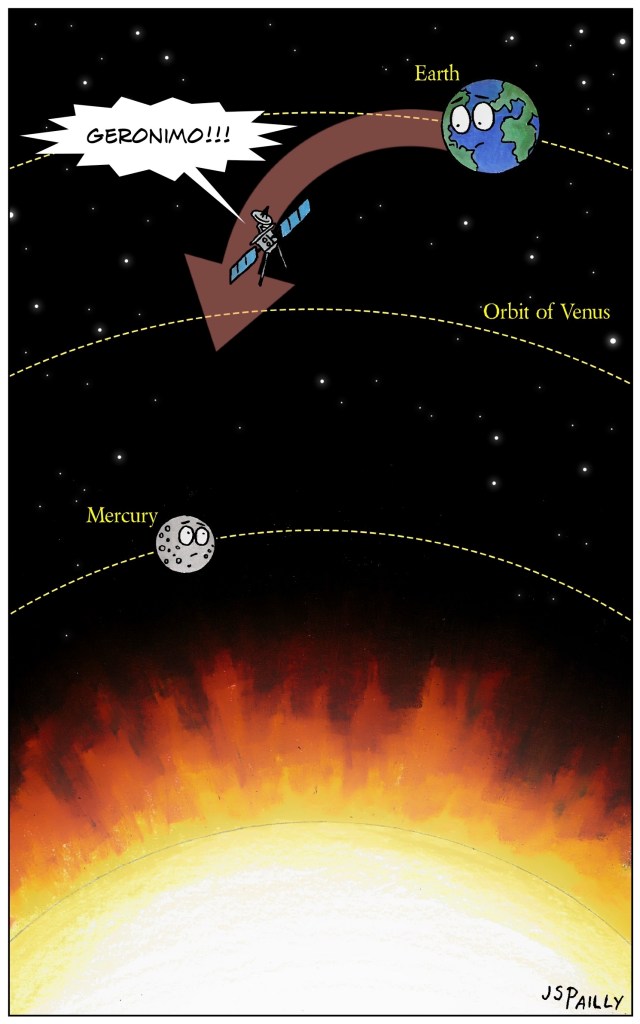

And yet, despite the fact that Mercury is so close to Earth so much of the time, Mercury is still one of the absolute hardest places for Earth-launched spacecraft to reach. The problem is the Sun. The Sun is very big, and the gravitational pull of the Sun is very strong. For our purposes, imagine that the Sun is “down,” and you’ll start to see what the problem is. Flying to Mercury is an awful lot like falling toward the Sun.

Now I do want to acknowledge that I’m glossing over a whole lot of technical details here. The purpose of this blog post is not to teach you the science and mathematics behind orbital mechanics. All I want is to give you a small taste of what makes flying to Mercury so very challenging, so that you can better appreciate the amazing accomplishments of NASA’s Mariner 10 and MESSENGER Missions.

MARINER 10

NASA’s original plan for Mariner 10 was to aim carefully and fly by Mercury one time. A certain Italian astronomer had a better idea, involving a never-before-attempted gravity assist maneuver near Venus. This tricky maneuver allowed Mariner 10 to perform three flybys of Mercury for the price of one.

Gravity assist maneuvers, where a spacecraft uses a planet’s gravity to make a “for free” course adjustment, are standard practice in spaceflight today, but Mariner 10 was the first to ever attempt such a thing. Mariner 10 was also the first spacecraft to visit two planets, collecting some data about Venus before continuing on its way to Mercury (Mariner 10 was also lucky enough to collect data from a nearby comet—another first in space exploration).

Mariner 10 flew by Mercury in March of 1974, September of 1974, and March of 1975. During those three encounters, Mariner 10 discovered Mercury’s magnetic field and Van Allen radiation belt. Mariner 10 also discovered Caloris Basin, Kuiper Crater, and many other important surface features. Unfortunately, only half of the planet was in daylight during Mariner 10’s three flybys, and it was always the same half of the planet, so the other half of Mercury remained unseen and mostly unknown for decades thereafter.

Shortly after Mariner 10’s third flyby of Mercury, the spacecraft ran out of fuel for attitude control. Without attitude control, the spacecraft couldn’t keep its communications system pointed toward Earth. So before contact was lost, mission control ordered the spacecraft to shut down. The now defunct spacecraft is still, presumably, orbiting the Sun somewhere near the orbit of Mercury.

MESSENGER

MESSENGER is an acronym for MErcury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry, and Ranging. The name is also a reference to Mercury’s role in Roman mythology as the messenger of the gods. The MESSENGER Mission was funded through NASA’s Discovery Program, a highly competitive program for space missions that can be done on a tight and highly-restrictive budget.

MESSENGER launched on August 3, 2004. Unlike Mariner 10’s series of flybys, the plan for MESSENGER was to enter orbit of Mercury. This required a much longer and more intricate flight trajectory, with one gravity assist maneuver at Earth, two at Venus, and a series of three maneuvers at Mercury to help match Mercury’s orbital velocity. MESSENGER achieved Mercury orbit on March 18, 2011, after seven-plus years of travel.

Over the next four years, MESSENGER photographed the entire surface of Mercury (including the half of the planet Mariner 10 couldn’t see), continued to study Mercury’s magnetic field, and revealed Mercury’s internal structure through a process called gravity mapping, which involved measuring subtle variations in a planet’s gravitational field. Oh, and who could forget this? MESSENGER also discovered water on Mercury. Believe it or not, there is water (frozen as ice) inside craters around the north and south poles of Mercury.

In early 2015, MESSENGER ran out of fuel, and the spacecraft’s orbit around Mercury began to deteriorate. On April 30, 2015, MESSENGER finally crashed into the planet’s surface, giving the most heavily cratered planet in the Solar System one additional crater.

WHAT’S NEXT?

The work of NASA’s Mariner 10 and MESSENGER Missions will be continued by BepiColombo, a collaborative mission by ESA (the European Space Agency) and JAXA (the Japanese Aerospace eXplotation Agency). I wrote about BepiColombo in a previous post.

Now I want to correct something I’ve been saying about BepiColombo in previous posts. I’ve said that BepiColombo will arrive at Mercury in 2025; that’s not quite right. BepiColombo will enter Mercury orbit in 2025, but much like MESSENGER, BepiColombo needs to perform several gravity assist maneuvers near Mercury first. Two of those gravity assists have already happened, and during those maneuvers, BepiColombo already started snapping photos and gathering science data.

So every time this month that I said only two spacecraft have ever visited Mercury, that was incorrect. BepiColombo has already become Mercury’s third visitor.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

NASA has posted some nice articles about Mariner 10, MESSENGER, and BepiColombo on one of their educational websites. Click these links to check them out: