Hello, friends! Welcome back to Sciency Words, a special series here on Planet Pailly where we talk about those weird and wonderful terms scientists use. Today’s Sciency Word is:

HEARTBEAT TONE

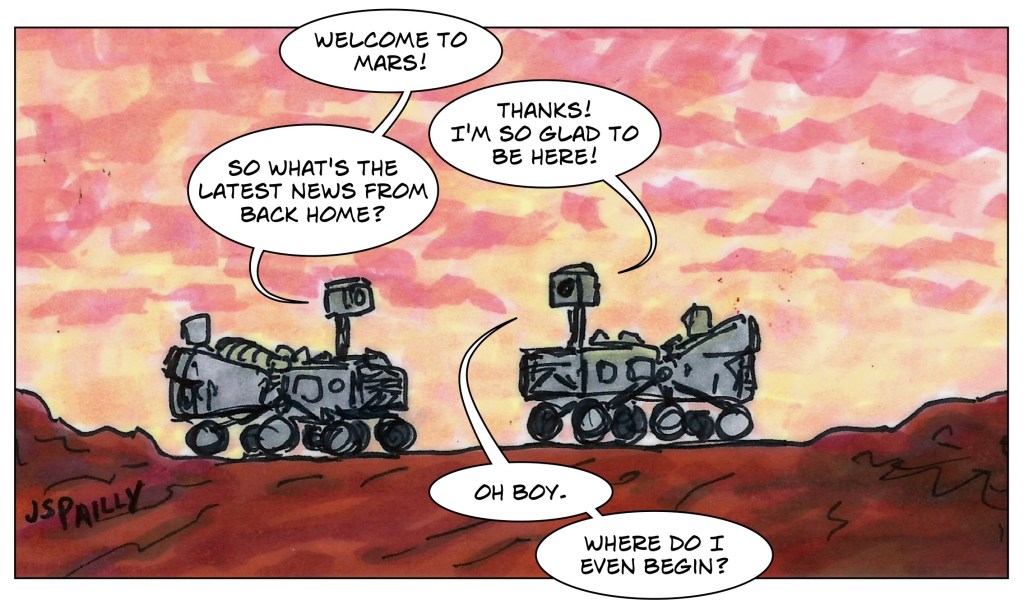

Last week, I watched NASA’s live coverage of the Perseverance rover landing on Mars. Naturally, I had a notepad ready, and I picked up quite a few new scientific terms. My absolute favorite—the one that brought the biggest smile to my face—was “heartbeat tone.” I love the idea that Perseverance (a.k.a. Percy, the Mars Rover) has a heartbeat.

As this article from Planetary News describes it, Percy’s heartbeat tone is “similar to a telephone dial tone.” It’s an ongoing signal just telling us that everything’s okay. Nothing’s gone wrong, and everything’s still working the way it’s supposed to.

Of course, other NASA spacecraft use heartbeat tones as well. According to two separate articles from Popular Mechanics, the Curiosity rover on Mars and the Juno space probe orbiting Jupiter also send heartbeat tones back to Earth. And that article about Juno offers us a little bit of detail about what Juno’s heartbeat actually sounds like: a series of ten-second-long beeps, sort of like very long dashes in Morse code.

Based on my research, it seems like the earliest NASA spacecraft to use heartbeat tones (or rather, the earliest spacecraft to have this heartbeat terminology applied to it) was the New Horizons mission to Pluto, which launched in 2005. As this article from Spaceflight 101 explains it, New Horizons’ onboard computers monitor for “heartbeat pulses” that are supposed to occur once per second. If these pulses stop for three minutes or more, backup systems kick in, take over control of the spacecraft, and send an emergency message back to Earth.

So, I could be wrong about this, but I think this “heartbeat pulse” or “heartbeat tone” terminology started with New Horizons. To be clear: I’m sure spacecraft were sending “all systems normal” signals back to Earth long before the New Horizons mission. I just think the idea of using “heartbeat” as a conceptual metaphor started with New Horizons. But again, I could be wrong about that, and if anyone has an example of the term being used prior to New Horizons, I would love to hear about it in the comments below!

P.S.: I recently wrote a post about whether or not planets have genders. With that in mind, I was amused to note in NASA’s live coverage that everyone kept referring to Perseverance using she/her pronouns. However, the rover has stated a preference for they/them on Twitter. So going forward, I will respect the rover’s preferred pronouns.