Hello, friends! Welcome to the second posting of this year’s A to Z Challenge! My theme this year is the planet Mercury, and in today’s A to Z post, the letter B is for:

BEPICOLOMBO

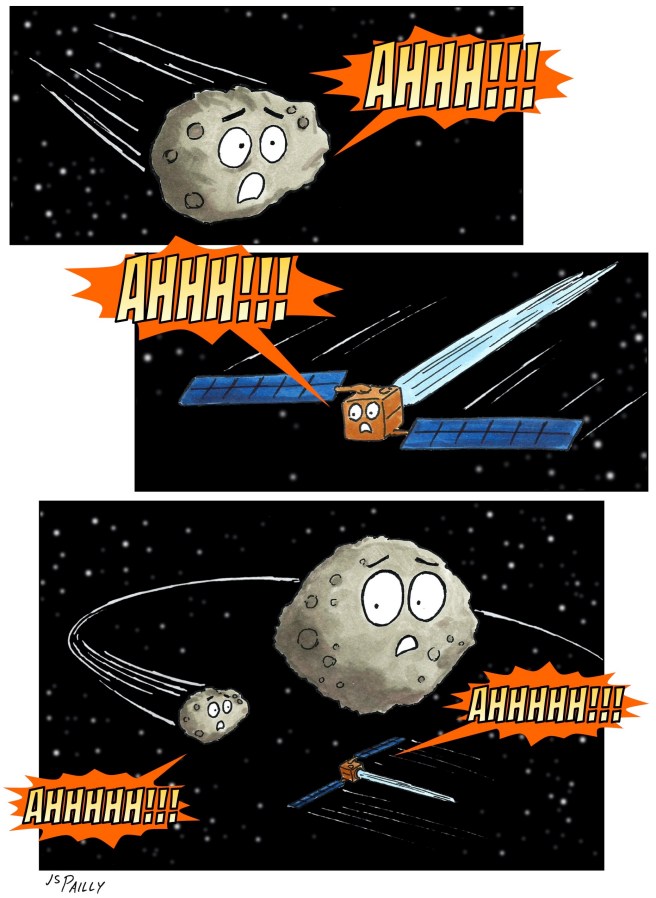

Mercury is a pretty lonely planet. Only two spacecraft have ever come to visit: NASA’s Mariner 10 space probe, which conducted a series of flybys in the 1970’s, and NASA’s MESSENGER Mission, which orbited Mercury for several years in the 2010’s. But don’t feel too bad. Soon, Mercury will be welcoming not one but two new guests, thanks to a joint mission by the European and Japanese space agencies. And that name of that mission? BepiColombo.

But first, a little history lesson. Back in the late 1800’s, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli determined that Mercury’s rotation rate (the time it takes for Mercury to spin on its axis) equals approximately 88 Earth days, or exactly one Mercurian year. Unfortunately, Schiaparelli’s calculations were way off (we’ll talk about that more in a future post), and it took another Italian scientist, named Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo, to fix Schiaparelli’s mistake.

In the 1960’s, thanks to new RADAR observations of Mercury, astronomers discovered that Mercury’s true rotation rate is approximately 59 Earth days, or precisely two-thirds of a Mercurian year. And I do mean precisely two-thirds of a Mercurian year. Odd coincidence, right? Don’t worry. We’ll talk about that more in future posts, too. For now, all you need to know is that Giuseppe Colombo was the lead author on a paper that explained how Mercury could have gotten itself into this rather curious predicament.

The history lesson’s not over yet! In the 1970’s, NASA was planning their first mission to Mercury, a mission known as Mariner 10. But getting to Mercury isn’t easy. Mercury is very small, and the Sun is very big. The orbital mechanics of approaching such a small object in space, so close to such a big object, are really complicated. NASA scientists thought the best they could do was aim carefully and do one quick flyby of Mercury. But NASA was wrong, and once again, Giuseppe Colombo stepped in to correct the mistake.

Colombo showed NASA an alternative flight trajectory, involving a never-tried-before gravity assist maneuver near Venus, which would cause Mariner 10 to fly past Mercury, circle around the Sun, then fly past Mercury again… and again! Thanks to Colombo’s orbital calculations, Mariner 10 was able to do three flybys of Mercury for the price of one.

Fast forward to modern times. When ESA (the European Space Agency) and JAXA (the Japanese Aerospace eXploration Agency) decided to team up for a Mercury mission, they had no trouble picking a name. In honor of Colombo’s outstanding contributions to the study and exploration of Mercury, the mission was officially named BepiColombo (one word, no space or hyphen—I’m not sure why it’s like that, but it’s one word).

BepiColombo is already in space, on route to Mercury. When it arrives in 2025, it will separate into two spacecraft: the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (M.P.O.), built by Europe, and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (M.M.O.), built by Japan. Together, these two spacecraft will follow up on some of the lingering mysteries about Mercury (i.e., other stuff that we’ll talk about in future posts).

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

I’m going to recommend this article from Univere Today, entitled “Who was Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo and Why Does He Have a Spacecraft Named After Him?”

I’m also going to recommend this article from the Planetary Society, entitled “BepiColombo, Studying How Mercury Formed.”

And for those of you who enjoy reading scientific papers for fun, like I do, here is Giuseppe Colombo’s original research paper from 1965, explaining how Mercury’s rotation rate ended up being precisely two-thirds of a Mercurian year.

So as we end our month-long adventures with the Sun, let’s give a big round of applause to the SOHO spacecraft, one of the hardest working spacecraft in the Solar System, and let’s hope that it will miraculously keep working for many years to come.

So as we end our month-long adventures with the Sun, let’s give a big round of applause to the SOHO spacecraft, one of the hardest working spacecraft in the Solar System, and let’s hope that it will miraculously keep working for many years to come.