Hello, friends, and welcome to this month’s meeting of the Insecure Writer’s Support Group. If you’re a writer, and if you feel in any way insecure about your writing life, click here to learn more about this amazingly supportive group!

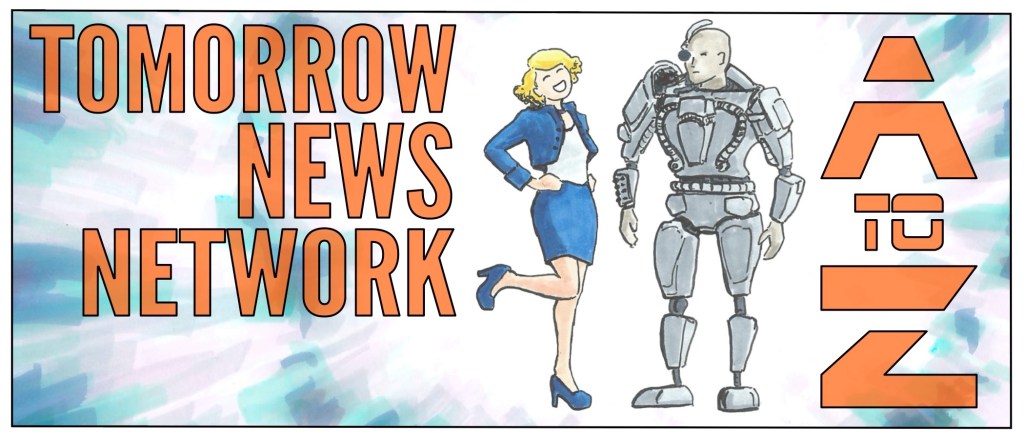

I don’t know about you, but my writing productivity crashed and burned toward the end of March. Right now, I’m feeling insecure because I’ve done virtually nothing to prepare for this year’s A to Z Challenge. I’m also feeling insecure because the timeline for publishing Tomorrow News Network, book one, has totally fallen apart.

I have no one to blame but myself. Wait, no, that’s not true. The coronavirus deserves a lot of the blame too. Not all of the blame, but a lot of it.

So here’s my plan. Even though I’m as ill-prepared for the A to Z Challenge as I could possibly be, I’m doing the challenge anyway. My theme is the story universe I created for Tomorrow News Network. Obviously, I have an ulterior motive for doing this. It’s my way of saying: “Buy my book!”

Except the first book of the Tomorrow News Network series isn’t out yet. It won’t be released until (checks timetable, mutters curse at the coronavirus)—okay, I still have to figure out what my new release date will be. But it’s coming soon!

I have a second ulterior motive as well. You see, book one is more or less finished, but I still have to write books two, three, four, five (etc, etc, etc). So as I tell you all about this fictional universe I’ve created, your feedback, dear reader, will be invaluable as I plan out the rest of the Tomorrow News Network series.

And lastly, my third ulterior motive may be the most important of all, given my current mental state during the coronavirus crisis. As I said at the beginning of this post, my writing productivity crashed and burned near the end of March, and I’m having a tough time getting back into my creative groove. I’m hoping that by participating in the A to Z Challenge—and by writing, specifically, about my own story universe—I’ll jumpstart my writing brain. I guess we’ll have to wait until the end of April to know if that works.

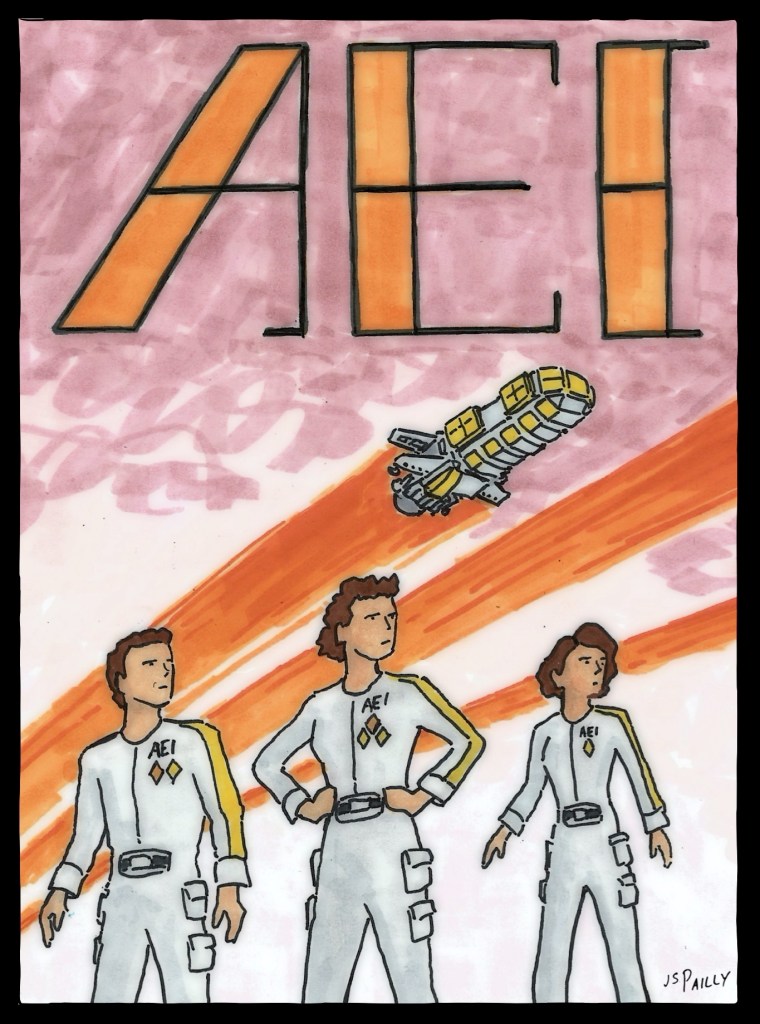

In the meantime, please click here to check out the first Tomorrow News Network: A to Z post. Today, A is for Alkali Extraction Incorporated, a faceless mega-corporation that’s mining alien planets for their resources.