Hello, friends!

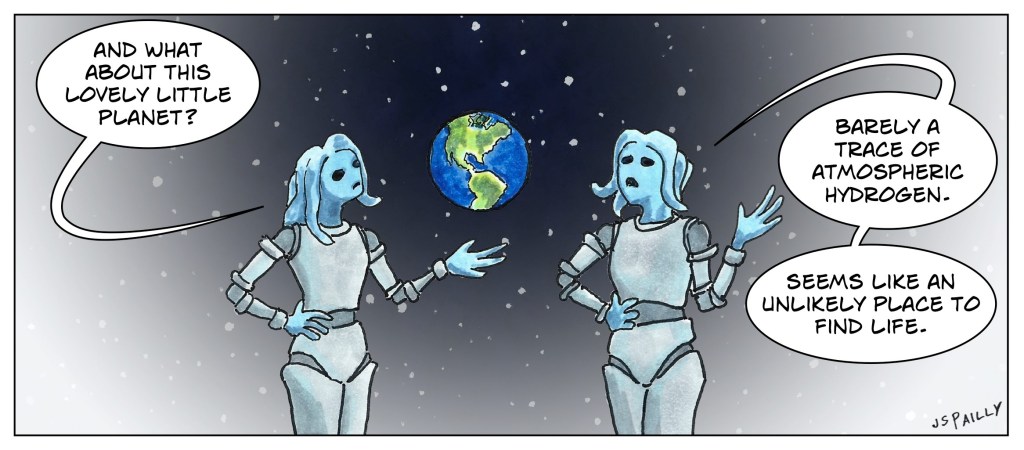

So let’s imagine that extraterrestrials don’t breathe oxygen. Oxygen is a pretty dangerous chemical, after all, so there’s good reason why alien organisms might want to avoid it. But what would these aliens breathe instead?

A few years back, I came across an interesting “fact” on a conspiracy theory website. The government doesn’t want you to know this, but apparently a lot of alien species breathe hydrogen. That conspiracy theory website said a lot of weird and wacky things, but this hydrogen-breathing alien idea… based on what I know about chemistry, that idea kind of made sense to me.

You see we Earthlings use oxygen to oxidize our food. This oxidation reaction generates the energy we need to stay alive. But oxidation reactions are sort of equal-and-opposite to reduction reactions. Oxygen is a powerful oxidizing agent, obviously, but hydrogen? Hydrogen is a pretty effective reducing agent.

A paper published earlier this year examined the possibility of Earth-like planets with hydrogen-rich atmospheres. Such planets could, in theory, exist, but they’d have to meet one or more of the following criteria:

- The planet would have to be much colder than Earth (think Titan or Pluto-like temperatures).

- The planet would have to have much higher surface gravity than Earth.

- The planet would have to continuously outgas hydrogen from some underground source (subsurface reservoirs of water ice mixed with methane ice might do the trick).

If one or more of these conditions are not met, then a hydrogen-rich atmosphere would quickly fizzle out into space through a process called Jeans escape.

Now, could life exist in that sort of hydrogen-rich environment? The answer is yes. Absolutely yes. Even here on Earth, there are organisms that “breathe” hydrogen and use it to generate energy through reduction reactions. These organisms can be found deep underground, or clustered around deep-sea hydrothermal vents, or in other exotic niche environments where hydrogen is plentiful and oxygen is rare.

The real question is: could hydrogen-breathers evolve into complex, multicellular life forms? Earth’s hydrogen-breathers are mere microorganisms. Their version of respiration is nowhere near as efficient as the oxygen-based system we humans and our animal friends use. The inefficiency of hydrogen-based respiration has stunted the evolutionary development of Earthly hydrogen-breathers.

But maybe on another planet—a planet with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere unlike anything Earth has ever seen—maybe complex multicellular life could evolve on a planet like that. Maybe.

It’s plausible enough for science fiction, at least.