Hello, friends!

I may lose some geeky street cred by admitting this, but I don’t have the Litany Against Fear from Dune memorized. I can get through the first two or three lines, but after that I get the words all muddled up, and then I usually just trail off into silence. That’s a shame, because I’ve heard that the Litany really does help people cope with extreme fear and anxiety.

Before I talk about the Litany Against Fear and why it apparently does work (at least for some people), I want to acknowledge the fact that fear is not always a bad thing. There’s a scene from Star Trek: Voyager that’s stuck with me over the years, a scene where Captain Janeway confronts an alien being who is supposed to be the living embodiment of fear. When speaking to this being, Janeway has this to say:

I’ve known fear. It’s a very healthy thing, most of the time. You warn us of danger, remind us of our limits, protect us from carelessness. I’ve learned to trust fear.

People who are or who claim to be totally fearless are, in my mind, kind of stupid. There really are things in this world to be afraid of. But sometimes fear gets out of hand, either inhibiting us in our daily lives or causing us to react to perceived threats in ways that are harmful, both to ourselves and to others.

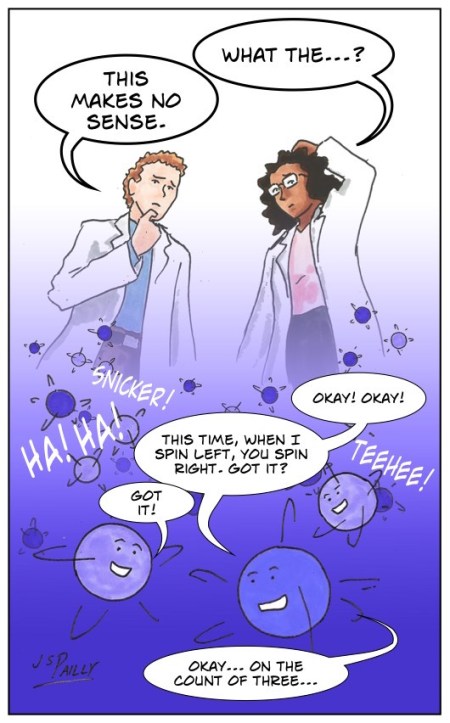

This brings us to something called the “amygdala hijack.” The term was coined in 1995 by American psychologist Daniel Goleman, and it refers to the way the amygdala (a part of the brain associated with, among other things, fear) can sometimes override our more logical brain functions. Once the amygdala perceives a threat (real or otherwise), it can hijack control over the rest of our brains and throw us into an immediate fight/flight/freeze response.

Earlier this year, I spent some time talking to a therapist. Some family stuff was going on, and I needed help processing it all. My therapist and I ended up talking a lot about the amygdala hijack, and I learned that it is possible to stop an amygdala hijacking in progress or prevent it from happening in the first place. It doesn’t take much. On one occasion, I tried simply saying out loud, “Hey amygdala, cut it out!” That actually worked.

There are also mindfulness exercises you can try. Reciting a prayer or mantra may also help. Or you could try using the Litany Against Fear. A few people have told me that the Litany really does work, and given what I’ve learned about the amygdala hijack, I can totally see why. First off, the Litany calls direct attention to what your amygdala is doing: mind-killing. Taking the time to recite the rest of the Litany then gives your brain the time it needs to recover. Several sources I’ve looked at mention that it takes about six seconds for the rational part of your brain to reassert itself after an amygdala hijacking. The Litany is just a bit longer than six seconds.

Maybe it’s finally time I memorized the Litany Against Fear in full.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Check out some of these articles:

“Why Dune’s Litany Against Fear is Good Psychological Advice” from Forbes.com.

“Amygdala Hijack: When Emotion Takes Over” from Healthline.

“Six Seconds to Emotional Intelligence” from Albertus Magnus College Blog.