I’ve been working hard this year to understand the secret world of amino acids. But amino acids are kind of useless all by themselves. It’s the way they join together that makes them so vitally important for life, or at least for life on Earth.

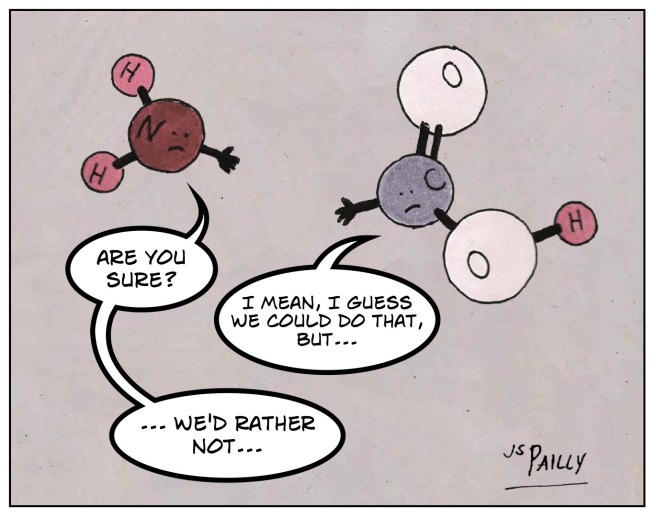

We’ve already looked at the anatomy of an amino acid. For today’s post, the crucial components are the amino group of one amino acid and the carboxyl group of another.

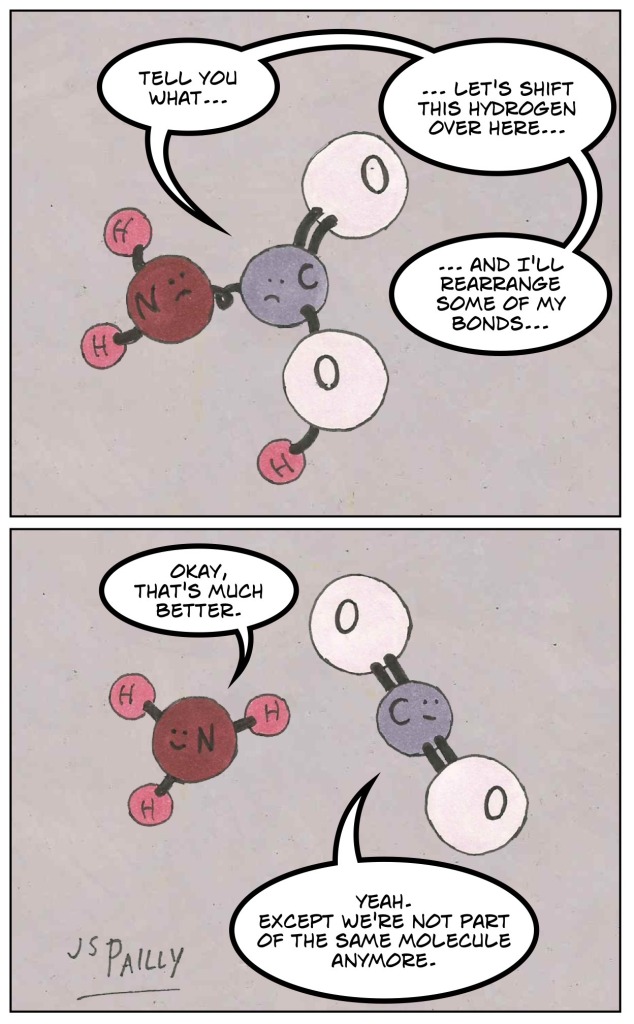

First, we remove one oxygen atom (the red ones) from the carboxyl group and two hydrogens (the white ones) from the amino group. One oxygen plus two hydrogens equals a water molecule: H2O.

Next, the carbon (in grey) in the carboxyl group reaches out for the nitrogen (in blue) in the amino group. When the two come together, they form what’s called a peptide bond.

This can happen over and over and over. One amino acids links up with another, which in turn links up with a third, which links with a forth and a fifth and a sixth….

I said at the beginning of this post that amino acids are kind of useless by themselves. That’s not quite fair. They can do plenty of fun, interesting chemistry on their own; but it’s this ability of theirs to form long peptide chains that makes them so useful (especially in a structural sense) for living organisms.

It’s entirely possible, in this big, wide universe of ours, that life exists without amino acids. But life without peptide bonds or something similar? Life without some easy way to string molecules together? Why, that would be pure science fiction!

P.S.: Or pure science fantasy, depending on how you define those terms.