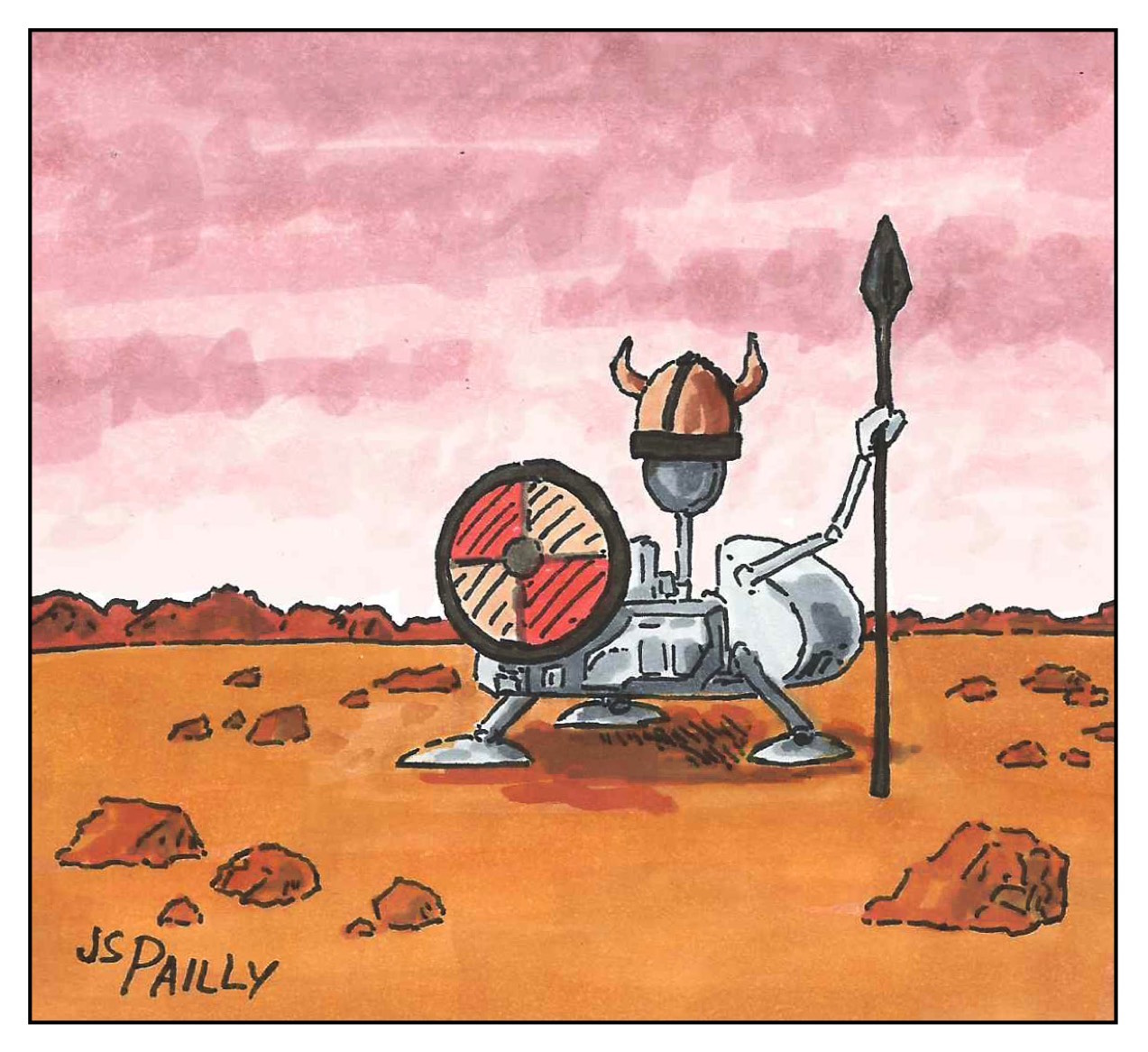

Welcome to a special A to Z Challenge edition of Sciency Words! Sciency Words is an ongoing series here on Planet Pailly about the definitions and etymologies of science or science-related terms. In today’s post, V is for:

VIKING

You know, I’ve noticed something about those early pioneers in the field of astrobiology. They thought they knew an lot about what aliens would be like, how aliens would behave. It seems awfully presumptuous in hindsight. People even thought they knew how alien microorganisms would behave.

In the late 1960’s, NASA was putting together a mission to Mars, and they decided to name this new mission Viking.

As explained in this book on NASA’s history of naming things:

The name had been suggested by Walter Jacobowski in the Planetary Programs Office at NASA Headquarters and discussed at a management review held at Langley Research Center in November 1968. It was the consensus at the meeting that “Viking” was a suitable name in that it reflected the spirit of nautical exploration in the same manner as “Mariner” […].

In NASA’s early years, nautical exploration was the theme for naming all missions to other planets.

The Viking 1 and Viking 2 landers arrived on Mars in 1976. They were the first space probes to successfully land (as opposed to crash) on Mars, and they were the first to send back photos from the surface. They were also the first, and so far the only, space probes to conduct experiments directly testing for Martian life.

And one of those tests came back positive!!!

Except it may have been a false positive. It was probably a false positive.

This test was called the labeled release experiment, and here’s how it worked: the Viking landers scooped up some Martian soil and added a nutrient mix—in other words, we tried to feed the Martians. The nutrient mix was “labeled” with a radioactive carbon isotope, so if any Martian microbes were living in the soil, they’d take the food and then release gaseous waste that had this special isotope in it.

But there were some problems with this idea. How do we know what Martian microbes eat? How do we know what waste products they produce? And—here’s the biggest problem of all—given how little we knew about Mars at the time, how do we know our nutrient mix wouldn’t react with some previously unknown chemical in the Martian soil, giving us a false positive result?

These are the kinds of questions that were asked after the labeled release experiment took place (but apparently not before). As a result, there was wild disagreement about what that positive test result might actually mean. The general consensus today is that we got a false positive. Our nutrient mixture must have reacted with something in the soil, something that was not alive.

But while the Viking Mission could not give us a definitive answer about whether or not there is life on Mars, Viking still taught astrobiologists a valuable lesson. When exploring strange, new worlds, trying to tell the difference between chemistry and biochemistry can be really hard.

Next time on Sciency Words A to Z, wow… just, wow!

It’s always encouraging to know that the “big scientists” are fumbling around for answers in the beginning too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True, and they made mistakes. The important thing is they learned from their mistakes, and I think more recent experiments on Mars have been better designed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never thought about the chemistry-biochemistry distinction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It creates an interesting problem, doesn’t it? If you don’t know what sort of chemistry is “normal” for another planet, how can you tell when you find something “special” that might indicate life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And for all we know, our idea of what constitutes life may be naive and narrow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very true.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m (just) old enough to remember the first Viking mission. It made a huge impression on my young self. We sent a spaceship to another planet!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That must’ve been an incredible feeling! Viking was only a few years before my time, unfortunately. I don’t know if any of the more recent space missions truly compares to that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was 8 years old. The first moon landing must have been amazing too. Unfortunately my only comments on that great event were, ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting post and I love your take on the Viking!

DB McNicol, author

A to Z Microfiction: Vase

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! That drawing was a lot of fun. Some ideas are too silly not to draw.

LikeLike