Hello, friends!

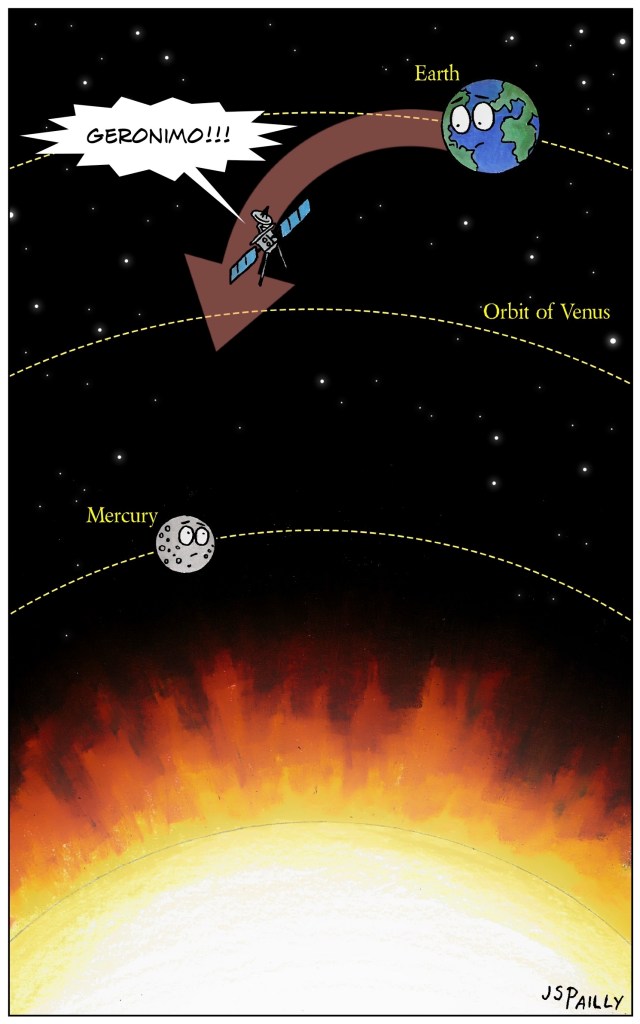

I don’t like to go out shopping. My time is valuable. Traffic is frustrating. Fuel is expensive. So if I do need to go out for some reason, I plan my route carefully and try to combine multiple errands into one trip. Believe it or not, this is a lifeskill that I learned from NASA. When NASA plans missions into outer space, they too plan carefully and try to double, triple, or quadruple up science objectives for a single mission.

In April of 2022, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences advised NASA to send a mission to the planet Uranus, with a launch date in the early 2030’s. This mission has not been officially approved yet, nor has it officially been named. As a placeholder name, it’s often called the Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission, or U.O.P. As this placeholder name implies, the mission would include two spacecraft: an orbiter, to orbit Uranus, and a probe, which would be dropped into the atmosphere to probe Uranus’s interior.

No spacecraft from Earth has visited Uranus since the 1980’s, so a mission like this is long overdue. The orbiter will spend four to five years orbiting the planet, studying the planet’s rings, measuring the planet’s weird and wonky magnetic field, and visiting all of the planet’s major moons—several of which may contain subsurface oceans of liquid water. Oh, and if NASA does launch in the early 2030’s, U.O.P. should arrive in time to observe the changing of seasons on Uranus (something which only happens once ever 42 years).

As for the atmospheric probe, it will spend maybe an hour or so plummeting through the planet’s atmosphere before being crushed by the increasing atmospheric pressure. Right now, scientists can only make educated guesses about Uranus’s interior structure and chemical composition. The uppermost layer of the Uranian atmosphere is an opaque haze of hydrocarbons. Neither ground-based nor space-based telescopes can see through that haze, so an atmospheric probe is the only way to find out what the deeper layers of Uranus’s atmosphere are really like.

But as I said at the beginning of this post, NASA likes to double, triple, and quadruple up science objectives whenever they can, and I just read about a really interesting and exciting side quest U.O.P. may be able to complete while on route to Uranus. For about a decade now, scientists have suspected that we might have nine planets in our Solar System after all.

According to the Planet Nine hypothesis, something very massive—massive enough to be a large planet or, perhaps, a small black hole—is lurking in the outer reaches of the Solar System, somewhere far beyond the orbit of Neptune. You see, the orbits of many of trans-Neptunian objects (comets, dwarf planets, etc.) seem to be clustered together in a rather peculiar way. It’s almost as if a very big, very massive something has been pushing all those trans-Neptunian objects around, corralling them together with the power of its gravity.

As of yet, no one has been able to pinpoint the exact location of the mysterious Planet Nine. But U.O.P. may be able to help! Remember that Uranus is very, very far away. The flight from Earth to Uranus will take a very, very long time. During that long journey through space, U.O.P. will feel the gravitational influence of all the planets in the Solar System—including the gravitational influence of any planets we don’t currently know about. So by keeping close tabs on U.O.P.’s exact location in space, astronomers should be able to notice any unexpected gravitational forces that may start tugging on U.O.P.

Even a slight gravitational tug should, over the course of the long journey to Uranus, be enough to point us in the direction of Planet Nine, or at least help us zero in on Planet Nine’s most probable location.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Here’s a write-up from the Planetary Society about NASA’s most recent “decadal survey” for planetary science, which includes (among other recommendations) the proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe Mission.

And here’s the research paper I read pitching the idea of using U.O.P. to help search for Planet Nine.

And lastly, here’s an article from Inverse explaining the above mentioned research paper in layperson’s terms.