Hello, friends!

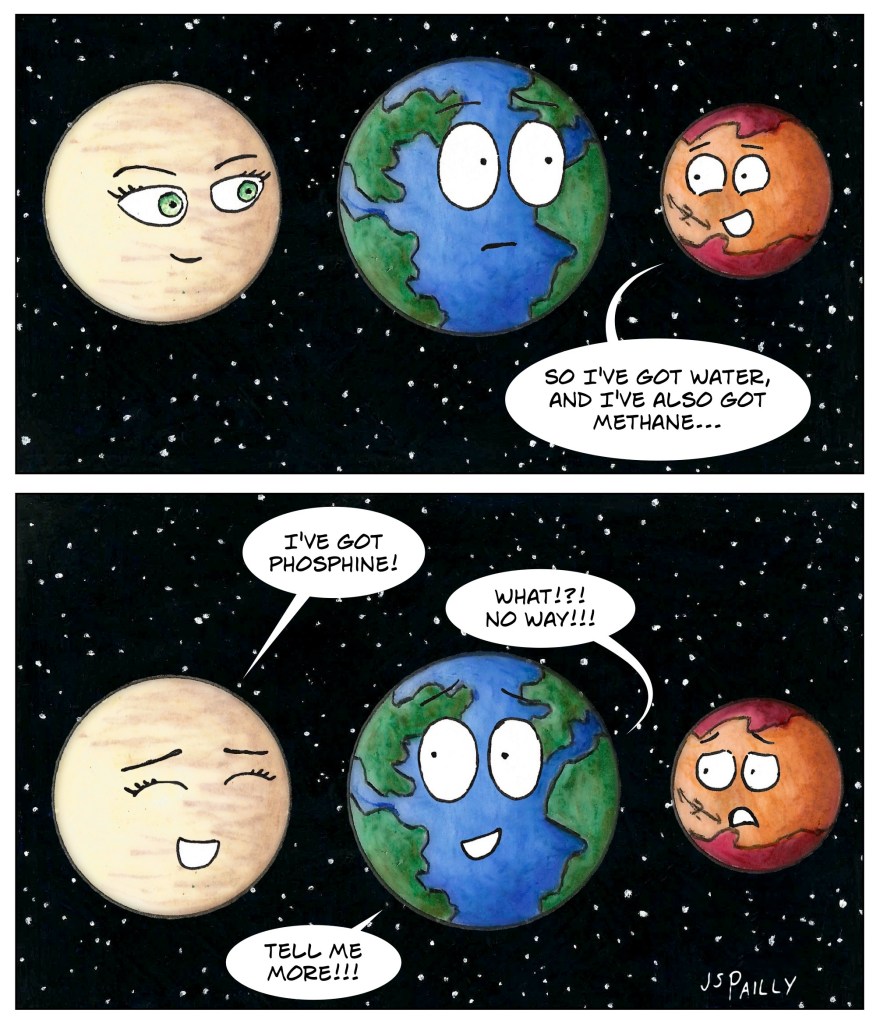

Over the last decade or so, Mars has been trying really hard to convince us that he can (and does) support life. We’ve seen evidence of liquid water on the Martian surface, and traces of methane have been detected in the Martian atmosphere. These things are highly suggestive, but none of that proves Martian life exists.

It would be nice if we knew of a chemical that clearly and unambiguously proved that a planet has life, wouldn’t it? According to this paper published in Nature Astronomy, phosphine (chemical formula PH3) might be the clear and unambiguous biosignature we need. Here on Earth, phosphine gas is a waste product produced by certain species of anaerobic bacteria. It’s also produced by humans in our factories. Either way, the presence of phosphine in Earth’s atmosphere is strong evidence that there’s life on Earth.

And according to that same paper from Nature Astronomy, astronomers have now detected phosphine on another planet. No, it wasn’t Mars.

Okay, we humans do know of non-biological ways to make phosphine, but they’d require Venus to be a very, very different planet than she currently is. For example, Venus would need to have a hydrogen-rich atmosphere, or Venus would have to be bombarded constantly with phosphorus-rich asteroids, or the Venusian surface would have to be covered with active volcanoes (more specifically, Venus would need at least 200 times more volcanic activity than Earth).

None of that appears to be true for Venus, so we’re left with two possibilities:

- There is life on Venus.

- There’s something we humans don’t know about phosphine, in which case phosphine is not the clear and unambiguous biosignature we hoped it was.

In either event, Venus is about to teach us something. Maybe it’s a biology lesson. That would be awesome! Or maybe it’s a chemistry lesson. Personally, I’m expecting it to be a chemistry lesson. There must be some other way to make phosphine that we humans never thought of.

P.S.: Now I’m sure a lot of you are thinking: “Wait a minute, don’t Jupiter and Saturn have phosphine in their atmospheres too?” You’re right. They do, and we’ll talk about that in Wednesday’s post.