Hello, friends!

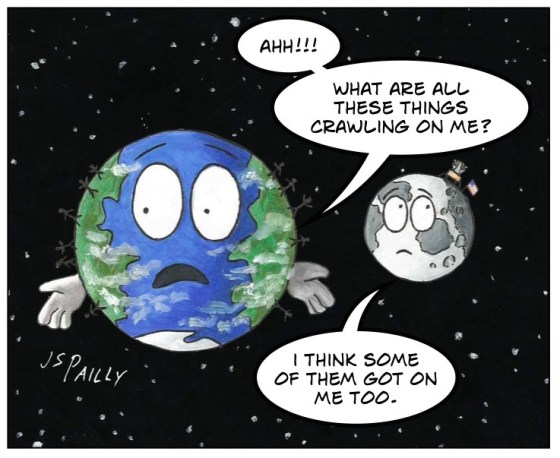

As some of you may already know, there is life on Earth. NASA discovered that fact in 1990. Let me explain.

In the decades prior to the Space Age, certain astronomers had claimed to observe vegetation growing on the Moon, artificial canals on the face of Mars, and some scientists even speculated that beneath the clouds of Venus (which were surely H2O clouds), we might find a world dense with jungle. Writers and philosophers had long speculated about how other worlds might be populated by other people, and at least a few theologians argued that there must be life on other planets (for why would God create all these planets and then leave them empty?).

And yet, as both the Soviet and American space programs ventured farther and farther out into space, they found nothing. No vegetation on the Moon (not even on the far side of the Moon). No canals on Mars. Definitely no jungles on Venus (and as for Venus’s clouds, it turns out they’re not made of H2O—they’re not made of H2O at all!!!).

I don’t want to make it sound like everybody expected to find life on the Moon, Mars, or elsewhere, but a lot of people were expecting to find life. So what happened? Why couldn’t our space probes find life on any of the other worlds of the Solar System? There were two possible explanations. Either there was no life out there to find, OR something was wrong with our space probes. Maybe they weren’t carrying the right equipment to detect life, or maybe they weren’t performing their experiments properly, or maybe they weren’t sending the correct data back to Earth.

Which brings us to 1990. NASA’s Galileo spacecraft was heading out to Jupiter, but for navigational reasons it needed to do a quick flyby of Earth first. A certain scientist named Carl Sagan saw this Earth flyby as an opportunity. What would happen if Galileo did a thorough scan of our home planet? Could this fairly standard NASA space probe, equipped with a fairly standard suite of scientific instruments, detect life on a planet where we already knew life existed?

The results were published a few years later in a paper entitled “A search for life on Earth from the Galileo spacecraft.” This “search for life on Earth” paper is my all time favorite scientific research paper. First of all, for a scientific paper, it’s a surprisingly easy read. Turns out Carl Sagan was a good writer with a knack for explaining science in a clear and accessible manner. Who knew? Secondly, the experiment itself is really cool. And third, the results of the experiment are a little more ambiguous than you might expect.

Among other things, Galileo detected both oxygen and methane in Earth’s atmosphere. If you didn’t already know there was life on Earth, it would be difficult to explain how those two chemicals could both be present. Oxygen and methane should react with each other. They should not exist together in the same planet’s atmosphere for very long—not unless something unusual (like biological activity) continuously pumps more oxygen and more methane into the atmosphere.

Additionally, Galileo noticed a strange “red-absorbing” substance widely distributed across Earth’s landmasses. This mystery substance could not be matched with any known rock or mineral, suggesting a possible biological origin. This red-absorbing mystery substance was, in fact, chlorophyll—the chemical that allows plants to perform photosynthesis.

And lastly, Galileo picked up radio transmissions. Galileo couldn’t determine the content of these transmissions, but the transmissions were clearly artificial—an indication that there is not only life but intelligent life on Earth.

I’ve read this “search for life on Earth” paper several times over the years. Like The Lord of the Rings or Ender’s Game, it’s one of those things I love to read again and again, and each time I feel like I get a little more out of it. The main take away, I have come to believe, is that if there were anything similar—anything even remotely similar—to Earth’s biosphere on the Moon or Mars or anywhere else in the Solar System, we would know about it. Our space probes would absolutely be able to detect something like that.

However, there’s still a lot of stuff here on Earth that the Galileo probe missed. Some little details, for example: chlorophyll absorbs both red and blue light, but Galileo apparently didn’t notice the blue absorption. Only the red. And Galileo overlooked some big things, too. Cities, roadways, the Great Wall of China? Maybe a follow-up mission to Earth would find those things, but Galileo didn’t see any of that stuff. And then there’s Earth’s oceans. Galileo couldn’t detect anything beneath the surface of the water. Water very effectively blocked all of Galileo’s sensors.

So our space probes are not fundamentally flawed, but they do have a few blind spots. Today, no one expects to find jungles on Venus or canals on Mars. Our space probes say those things aren’t there, and we can be confident that our space probes are working properly. But there are a few niche environments out there were alien life might still be hiding.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Science communicators (myself included) dumb things down for their readers, which is why reading actual scientific papers has become an important part of my research process. Dumbed down science is fine, provided it still says what the actual scientific research says. But reading these sorts of papers is a skill, and it takes some time and practice to do it. If you’ve ever wanted to start reading scientific papers for yourself, “A search for life on Earth from the Galileo spacecraft” by Carl Sagan et al. is a good starter paper.