Welcome to a special A to Z Challenge edition of Sciency Words! Sciency Words is an ongoing series here on Planet Pailly about the definitions and etymologies of science or science-related terms. In today’s post, B is for:

B.S.O.

When you study the planets, when you really get to know them well, you soon start to feel like they each have their own unique personalities. Jupiter is kind of a bully, pushing all the little asteroids around with its gravity. Venus hates you, and if you try to land on her she will kill you a dozen different ways before you touch the ground. And Mars… I can’t help but feel like Mars is kind of jealous of Earth.

I get the sense that Mars wishes it could be just like Earth, and that Mars is trying its best to prove that it has all the same stuff Earth has.

In 1996, Mars almost had us convinced. A team of NASA scientists led by astrobiologist David McKay announced that they’d found evidence of Martian life.

As reported in this paper, McKay and his colleagues found microscopic structures (among other things) within a Martian meteorite known as ALH84001. They interpreted those structures to be the fossilized remains of Martian microorganisms.

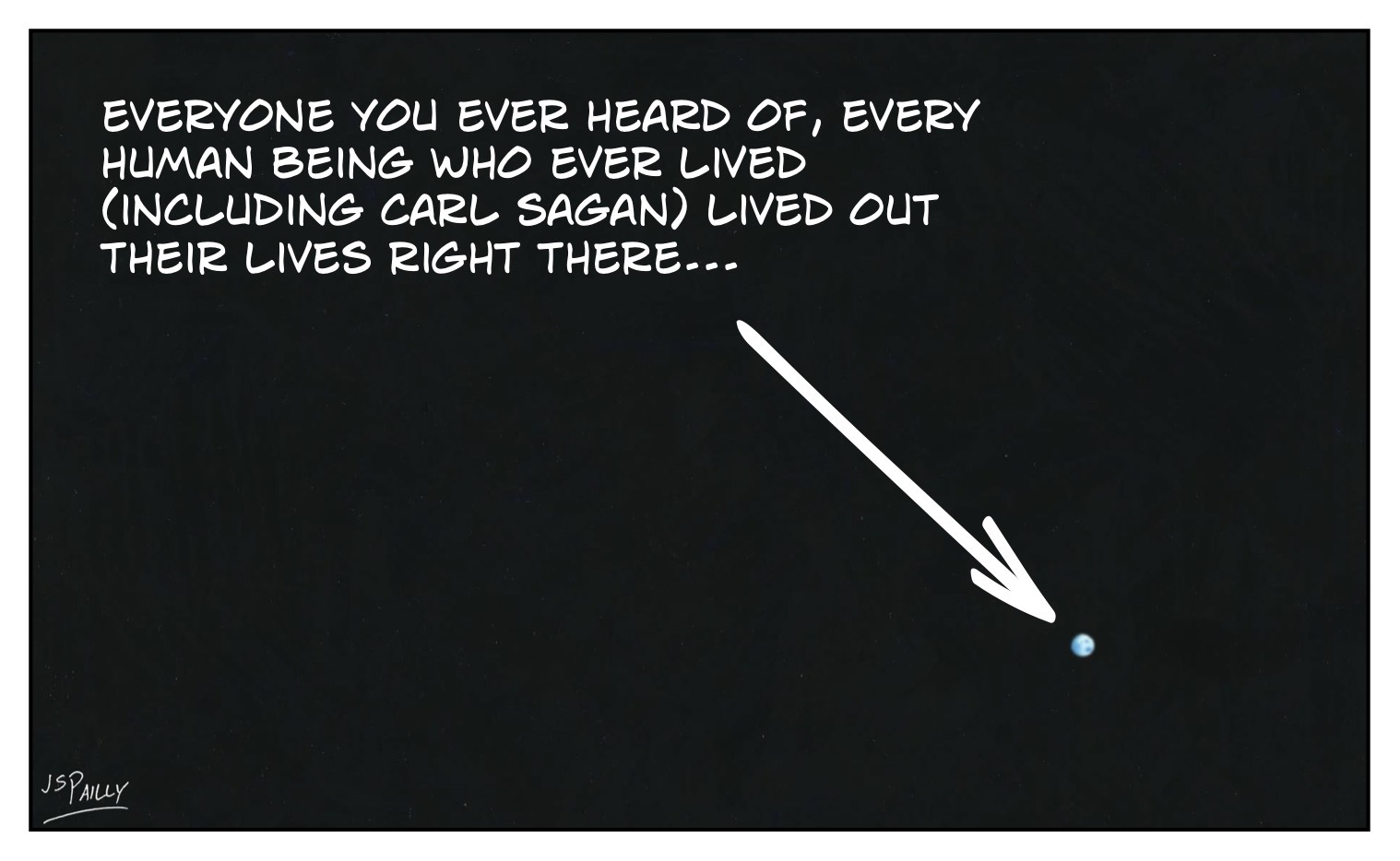

This was a truly extraordinary claim, but as Carl Sagan famously warned: “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Or to put that another way, when it comes to the discovery of alien life, astrobiologists must hold themselves and each other to the same standards as a court of law: proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

In follow-up research, those supposed Martian fossils came to be known as bacteria shaped objects, or B.S.O.s for short. I kind of wonder if somebody was being a bit cheeky with that term. I wonder if someone was trying to say, in a subtle but clever way, that the whole Martian microbe hypothesis was just B.S. As this rebuttal paper explains:

Subsequent work has not validated [McKay et al’s] hypothesis; each suggested biomarker has been found to be ambiguous or immaterial. Nor has their hypothesis been disproved. Rather, it is now one of several competing hypotheses about the post-magmatic and alteration history of ALH84001.

In other words, those B.S.O.s might very well be fossilized Martian microorganisms. Yes, they might be. It is possible. But no one has been able to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt, and therefore no one can say with any certainty that we’ve found evidence of life on Mars. At least not yet.

Still, the ALH84001 meteorite and its B.S.O.s are an important part of the history of astrobiology. As that same rebuttal paper says:

[…] it will be remembered for (if nothing else) its galvanizing effect on planetary science. McKay et al. revitalized study of the martian meteorites and the long-ignored ideas of indigenous life on Mars. It has brought immediacy to the problem of recognizing extraterrestrial life, and thus materially affected preparations for spacecraft missions to return rock and soil samples from Mars.

Next time on Sciency Words A to Z, are we prejudiced against non-carbon-based life?