Today’s post is a special A to Z Challenge edition of Sciency Words, an ongoing series here on Planet Pailly where we take a look at some interesting science or science related term so we can all expand our scientific vocabularies together. In today’s post, C is for:

CENTAUR

As I mentioned in my first Sciency Words: A to Z Challenge post, some scientific terms are kind of dumb. This isn’t one of them. I actually think this one’s pretty clever. There’s a class of large objects in the Solar System that astronomers have decided to call centaurs.

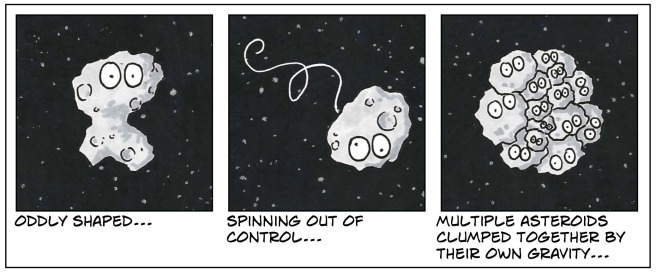

Eh… no. These objects have nothing to do with horses, but they are sort of half one thing and half another! When they were first discovered, astronomers were confused because centaurs appeared to have the characteristics of both asteroids and comets.

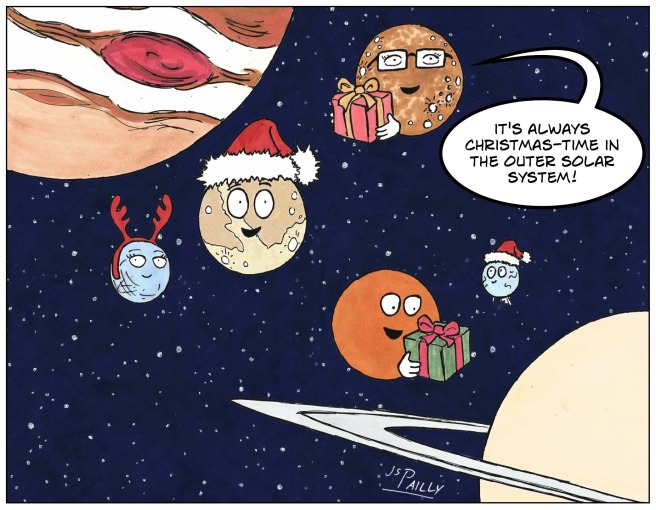

I first learned about centaurs in this article from Discovery News. It’s now believed that centaurs originally came from the Kuiper belt—a sort of second asteroid belt that lies beyond the orbit of Neptune. Basically, they came from Pluto’s neighborhood.

Due to gravitational interactions with the gas giants, these objects were pulled inward. The now have highly unstable orbits crossing between the orbits of Neptune and Jupiter. Eventually, further gravitational interactions may hurl a centaur into the inner Solar System, putting it within melting distance of the Sun and transforming it into a full-fledged comet.

Originally, the International Astronomy Union wanted to name all the centaurs after actual centaurs from Greek mythology. But they quickly ran out of names. Now the official naming theme includes all mythical hybrids and/or shape-shifters. Examples include Typhon (half man, half dragon), Ceto (half woman, half sea monster) and Narcissus (a man who transformed into a flower).

Next time on Sciency Words: A to Z Challenge, we’ll find out why dimetrodon is not a dinosaur.