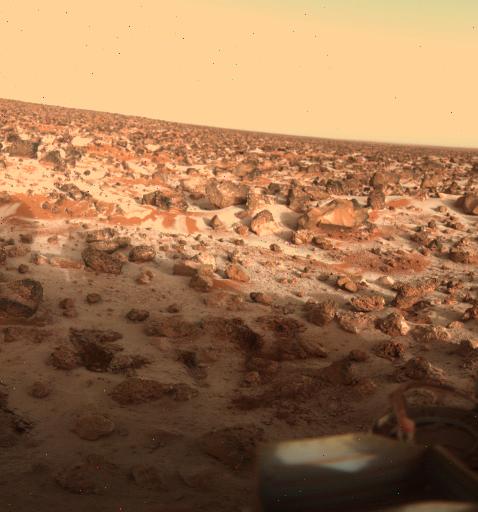

We’ve sent several robotic space probes to Mars already, and several more will be heading to the Red Planet in the next few years. Mars is already the second most heavily explored planet in the Solar System, after Earth.

But our robots are forbidden by international law from entering regions where Martian water appears to be flowing, or regions where Martian life could hypothetically exist. Why? Because there’s a chance that microorganisms from Earth hitched a ride aboard our space probes, survived the journey to Mars, and might start to grow and reproduce if they’re exposed to Martian water.

Yesterday, we talked about a paper in the journal Astrobiology which argued that the risk of contamination is minimal, and we should let our Mars rovers do their jobs. Go explore, and if there’s Martian life, go find it! Today we’re looking at a response to that paper, also published in Astrobiology, in fact in the same issue of Astrobiology. A response which raises several concerns, such as:

- In the last few decades, we’re learned that Earthly microorganisms can be far more resilient than we ever imagined. Some of them very well might survive—and thrive—on Mars.

- We’ve also learned that Mars is far less hostile to life than we previously assumed. Quite a few microbes from Earth might find Mars a rather comfortable place to live.

Taken together, these two points suggest that we have not overestimated the risk of contaminating Mars. In fact, we may have drastically underestimated the risks, and we need to be more careful, not less careful, about where we let our Mars rovers go. Otherwise:

- We might destroy the very Martian life forms that we’re so desperately hoping to find.

- We might make Mars’s water undrinkable for future human settlers.

- We might end up misidentifying a stowaway microbe from Earth as a new form of life native to Mars, and the authors of this response paper argue that even our best gene sequencing technology might not be able to clear up the potential confusion.

Even if our Mars rovers keep their distance from Mars’s potentially-habitable or potentially-inhabited areas, there’s still a lot of valuable science they can do, especially when they’re investigating areas that used to be lakes or rivers, areas that could have supported lots and lots of alien life in the past, even if they’re bone dry and very thoroughly lifeless in the present.

So let’s take things slow. Let’s stick to the original plan (and current international agreements) and continue to explore Mars in a responsible and methodical manner.

Or maybe not. Gosh, I don’t know. After reading these two papers back to back, I really don’t know what to think.