Hello, friends! It always seems like Mercury doesn’t get the same love and attention as the other planets, which is why I chose Mercury as my theme for this year’s A to Z Challenge. In today’s post, J is for:

JUMPING ON MERCURY

If you’re anything like me, you probably lie awake at night wondering what it would feel like to walk on another world. With each step, what would feel different, and what would feel the same? It’s the kind of thing you can read about, or you can watch videos from the Apollo era to see what walking on another world looks like. But to get the actual sensory experience of moving about in low gravity? I doubt I’ll ever get to experience that for myself.

But while I may never have the first hand physical experience of walking in low gravity, a few years back I read a paper that clarified some things for me, at least intellectually. The key thing to understand is that gravity helps you walk, more so than you probably realize.

When you take a step, you first lift one foot off the ground. This requires your muscles to do work. This takes energy. But when you put your foot down again, gravity helps you get your foot back down to the ground. Gravity makes it so your muscles don’t have to do quite as much work during your foot’s downward motion. Gravity saves you from expending just a little bit of extra energy as you finish taking a step. But if you’re on the Moon or Mars (or Mercury), there’s less gravity, and so your muscles get less help. It takes a little more energy than you might expect to put your foot back down to the ground.

This is why the Apollo astronauts ended up “loping” or “bunny hopping” all over the surface of the Moon. In interviews, the astronauts often said it just felt more natural and comfortable to move about that way. Scientifically speaking, it’s a matter of metabolic efficiency. Walking is a metabolically efficient way to get around on Earth, but without Earth-like gravity to help bring your foot back down to the ground, the metabolic efficiency of walking is diminished. The lower the gravity gets, the less efficient walking becomes, and if the gravity gets low enough, then skipping, hopping, and jumping start to feel, by comparison, a whole lot easier.

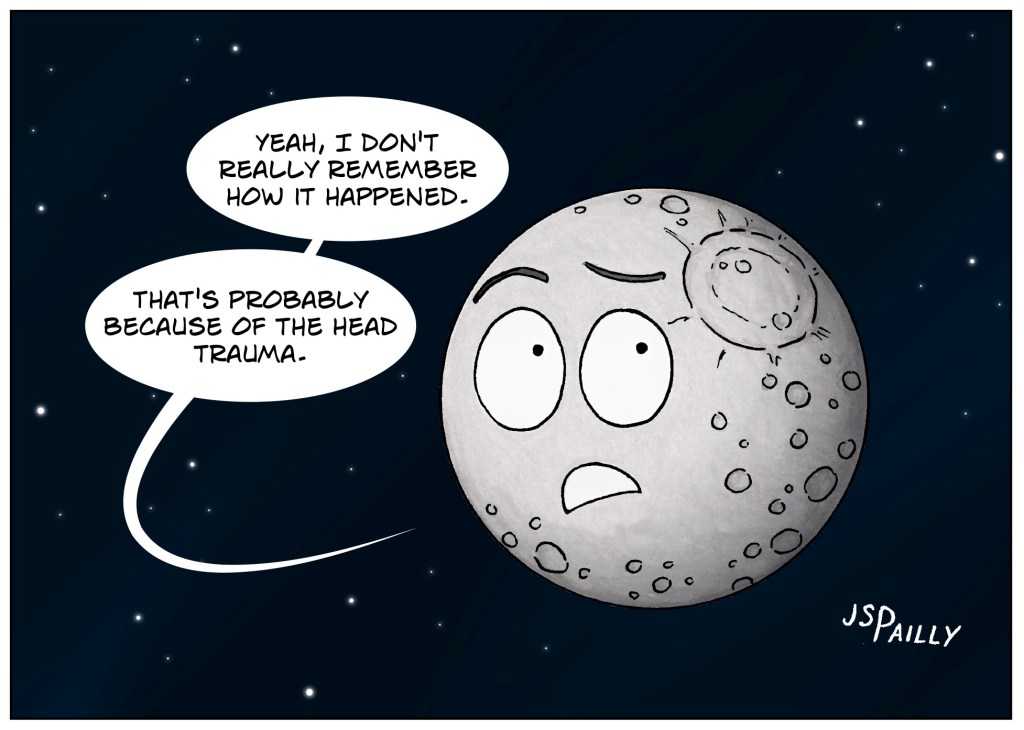

Mercury is about the same size as the Moon, but due to Mercury’s ginormous iron core, Mercury is a whole lot denser than the Moon. Higher density means higher gravity, and the surface gravity on Mercury is roughly twice the surface gravity on the Moon (or roughly the same as the surface gravity on Mars, even though Mars is a much larger planet). But Mercury-like (or Mars-like) gravity is still only one-third of the gravity we’re accustomed to here on Earth.

So if you ever want to go for a stroll on the surface of Mercury, first: remember to wear a spacesuit that can handle the extreme temperatures. And second, don’t feel embarrassed if you end up jumping, hopping, or skipping all over the place. It’s all for the sake of metabolic efficiency.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Here’s a short video from the Apollo era, showing astronaut Gene Cernan bunny hopping down a slope on the Moon while talking about how it is “the best way” to travel.

And here’s a short compilation of videos, also from the Apollo era, showing various astronauts tripping and falling all over themselves in lunar gravity.

And lastly, here’s the paper I mentioned, titled “Human Locomotion in Hypogravity: From Basic Research to Clinical Applications.” It’s not an easy read, but if you really want to understand what “human locomotion” would feel like on other worlds, this paper is the absolute best resource I’ve ever found.