Hello, friends! I have recently returned from a trip to see the 2024 solar eclipse (my first total solar eclipse!). I was traveling with a couple of friends. Due to weather-related concerns, we dropped our original plan to watch the eclipse in Buffalo, New York, and instead drove to a small town called Port Burwell, situated on the Canadian side of Lake Erie.

On the day of the eclipse, Port Burwell was the only place within hundreds of miles with a sunny forecast. Everywhere else was supposed to be cloudy or partly cloudy. Port Burwell’s forecast was sunny. We were not the only ones to realize this, and so we ended up being part of an enormous mob of people who descended upon this cute, lakeside town–a town that was very obviously not expecting so many people to show up. The locals were super nice, super welcoming, but also, very obviously, very surprised.

I wound up watching the eclipse from a concrete pier, with a cold (increasingly cold, once the event began) wind blowing on me from the lake. There have been only a few moments in my life where I felt like I’d been transported, body and soul, into another world: exploring the ancient cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde, seeing the bacterial mats at Yellowstone National Park, and standing on that pier in Port Burwell while the last light of the Sun flashed and vanished behind the Moon.

What happened next? Speaking as a writer, as a man of words, as a person who owns an absurd number of dictionaries and thesauruses, please understand what I mean when I say I have NO WORDS to describe the next three minutes. Strange? Beautiful? Terrifying, on some deep and primal level? Those words point in the general direction of what this experience felt like. And that’s the best I, as a writer, can offer. Sorry. Words fail me.

Although, there is one more word I would use to try to communicate what my eclipse experience was like. It’s the name of a color. Magenta. As it so happens, the 2024 eclipse occurred during solar maximum, the most active part of the Sun’s eleven year cycle. Several solar prominences (those giant, fiery arcs that rise up from the Sun’s surface) were visible to the naked eye during the eclipse. One extremely bright prominence appeared near the “bottom” of the Sun, and I saw two other large, flickering prominences on the Sun’s righthand side.

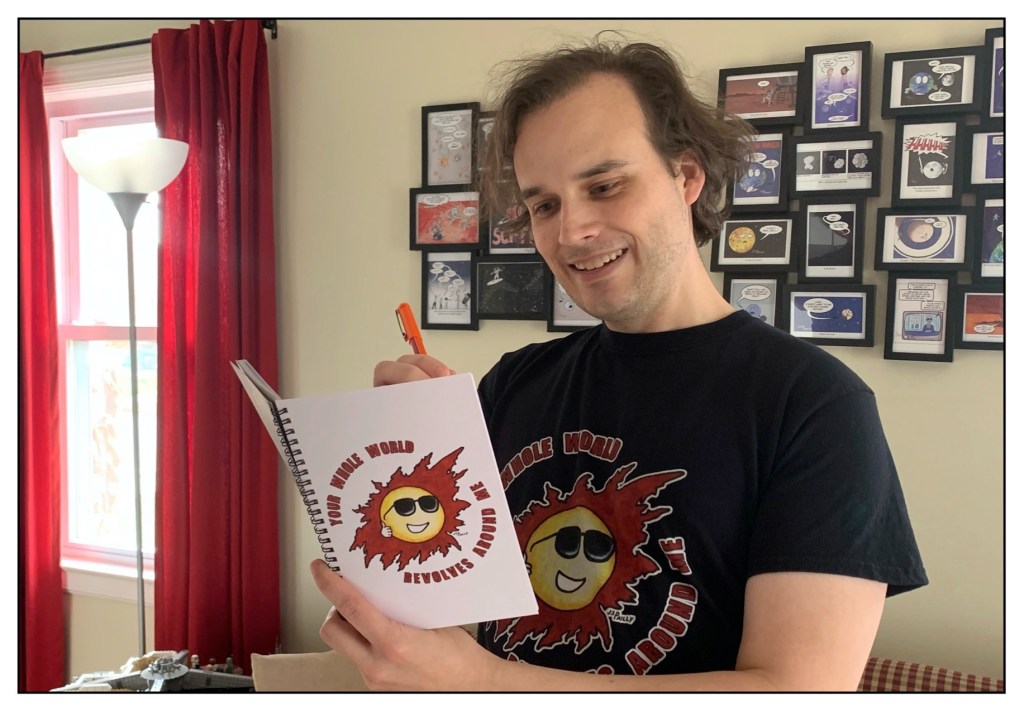

To my eye, the prominences were the most perfect magenta color I have ever seen in nature. It was like the pure magenta that computers generate in a CMYK color pallet. The next day, I decided to try drawing the eclipse based solely on my own memory (see the image above). Memory is an imperfect thing. In my drawing, it seems that I made the bottom and righthand prominences bigger than they really were (probably because those three prominences stand out so prominently in my memory). But the color is about right. That color is, I swear to you, the color that I saw. Which is strange, because my best friend, who was standing right next to me at the time and who was definitely seeing the same eclipse I was, swears the prominences were bright, bright red. Not magenta. Red.

After I drew my version of the eclipse, my friend used color correction software to try to approximate the color he saw. He tells me his version is still not quite right, but it’s close enough. So here’s the side-by-side comparison:

After comparing notes with a few other people who also saw the eclipse, it seems that most people (but not everyone) saw what my friend saw: a bright red color. One person went so far as to call it an orangey-red color. Only a few people saw the same magenta color I saw.

There’s so much about the eclipse that I did not expect, but this red vs. magenta thing is the part I expected the least. So I want to end this post by asking you, dear readers: did you see the eclipse? And if you did, what color were the solar prominences? Did they look red to you? Did they look magenta? Did you, perhaps, see a different color entirely?