Hello, friends!

Imagine a story involving G.M.O. crops, ChatGPT, the ebola virus, virtual reality gaming, an accident aboard the International Space Station, a submarine reported missing in the Marianas Trench, and a rogue militant group in possession of a hydrogen bomb. That’s an awful lot of science and technology packed into a single story, but is it a science fiction story? I’d say no. It would be one hell of a story—that’s for sure!—but it probably would not be a science fiction story.

So what is science fiction? There are so many proposed definitions out there, ranging from “an imaginative exploration of the relationship between scientific advancement and social progress” to “it’s that thing nerds like.” I’ve seen people argue that science fiction is just fantasy with a veneer of scientific language. I also once read that the ideal science fiction story should contain 25% science and 75% literature (which is why, whenever I write Sci-Fi, I always measure my science precisely).

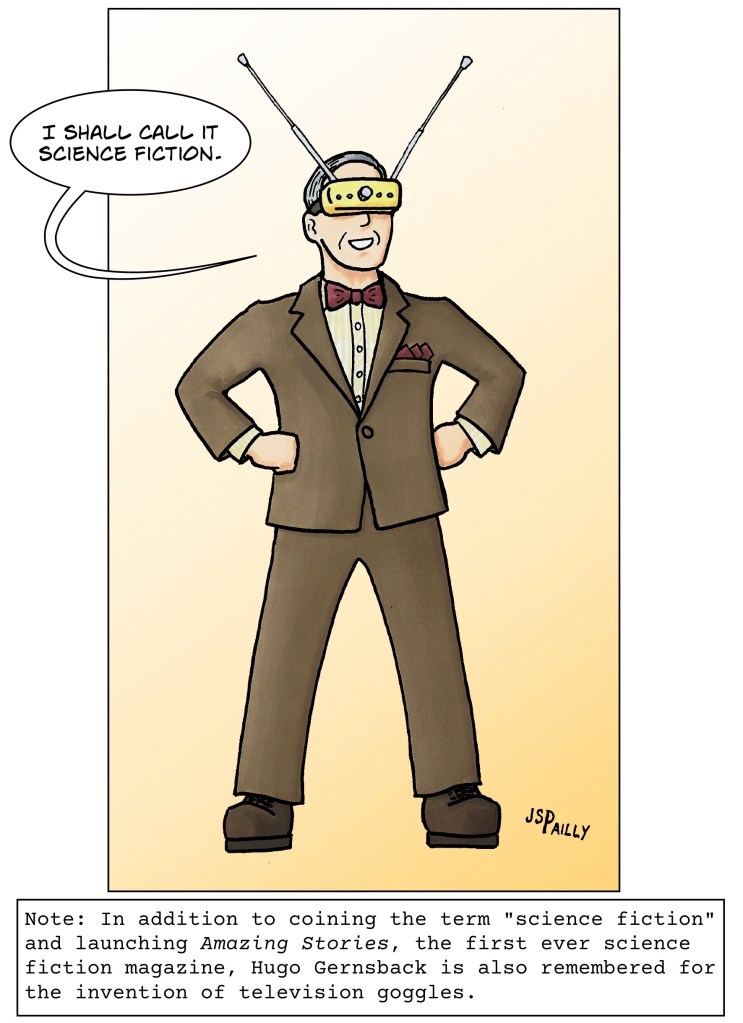

That 25% science thing actually comes from Hugo Gernsback, the man who generally gets credit for coining the term science fiction; or, if he didn’t actually coin the term, then he at least deserves credit for popularizing it as a genre label.

After years of reading about this and thinking about it and debating the topic with other science fiction enthusiasts, I’ve settled on my own personal definition of science fiction. Science fiction is any story where the plot depends upon fictional science.

I like this definition because it’s pithy. It’s easy to remember. More importantly, though, I think it works. Jurassic Park depends upon the fictional science of dinosaur cloning. Frankenstein depends on the fictional science of reanimating the dead. Isaac Asimov’s novels depend on multiple fictional sciences, like psychohistory and the three laws of robotics. And Star Trek depends on the fictional science of warp drive, quantum teleportation, holodecks, extraterrestrial intelligences, etc, etc, etc…. All of these stories may be inspired by real science, and they may touch on real scientific facts from time to time, but they also all depend on the fictional science parts. Remove the fictional science from any of the examples listed above, and the stories totally fall apart.

Going back to that absolutely insane story idea from the beginning of this post—yes, that story is packed with science. That story contains far more than 25% science, I’d say. But all the key plot points, from G.M.O. crops to the International Space Station to hydrogen bombs—all those things are real. The plot of that story may be a wild ride, but it doesn’t depend on any fictional science in order to work. Ergo, it’s not science fiction. It’s just regular fiction with a whole bunch of science mixed in.

Science fiction is about fictional science. Science fiction depends upon fictional science in order for the story to work. That’s the defining feature, at least in my opinion.

Want to Learn More?

Today’s post was prompted, in part, by a new series on Fiction Can Be Fun, examining speculative fiction in its various forms and flavors. Click here to read the first post in that series, and click here for the second post.

And did Hugo Gernsback really coin the term science fiction? There’s some dispute about that, and here’s a list of examples of people using the term before Gernsback introduced it. My stance on the issue is this: other people may have put the words “science” and “fiction” together before Gernsback, but Gernsback still deserves credit for first using the term “science fiction” as the name of a distinct genre of literature.

And lastly, do you want to know more about Gernsback’s television goggles? Click here!