Sciency Words: (proper noun) a special series here on Planet Pailly focusing on the definitions and etymologies of science or science-related terms. Today’s Sciency Word is:

KILONOVA

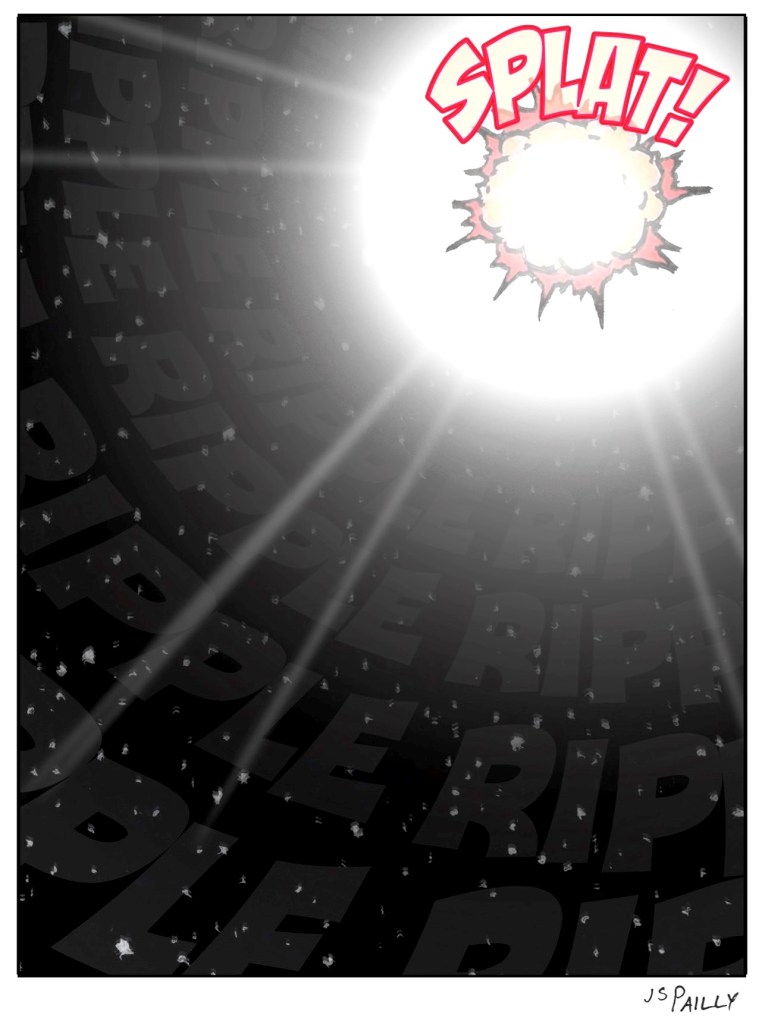

In a recent presentation at Princeton University, Dr. Beverly Berger—an astrophysicist from LIGO—used a very interesting term. Imagine a pair of neutron stars orbiting each other, spiraling closer and closer together, until suddenly “they go splat!” as Dr. Berger enthusiastically described it.

The more official-sounding term for this is kilonova, Dr. Berger then explained. The term kilonova originates from this 2010 paper, which predicted that the merger of either two neutron stars or a neutron star and a black hole would produce a very bright flash of light.

The authors of that paper calculated that, at peek luminosity, this flash of light would be approximately a thousand times brighter than a nova explosion—hence “kilonova.” (In case you’re wondering, a kilonova is still not as bright as a supernova—a supernova is “as much as 100 times brighter than a kilonova” according to this article from NASA.)

Of course the LIGO project is designed to detect gravitational waves, not bright flashes of light. But as you can see in the highly technical diagram below, a kilonova is accompanied by subtle ripples in the fabric of space-time—gravitational waves, in other words.

In August of 2017, the LIGO project detected exactly the kinds of ripples that would indicate two neutron stars had “gone splat.” As this article from the LIGO website explains, alerts were “sent out to the astronomical community, sparking a follow-up campaign that resulted in many detections of the fading light from the event, located near the galaxy NGC 4993.”

One thing I’m still not clear about: what happens after a kilonova? It seems the scientists at LIGO are wondering about that too. According to that same article from the LIGO website, the 2017 kilonova produced either the largest neutron star that we’ve ever observed OR the smallest black hole. “Both possibilities are tantalizing and fascinating,” the article says, “but our data simply isn’t good enough to tell us one way or the other.”

Fortunately there are a few projects in development that might help us understand kilonovae—and similar cosmic cataclysms—a little bit better. We’ll take a look at some of those upcoming projects in Monday’s post.