Sciency Words: (proper noun) a special series here on Planet Pailly focusing on the definitions and etymologies of science or science-related terms. Today’s Sciency Word is:

LOVE NUMBERS

My friends, I was recently doing research about the planet Neptune. Astronomers have a new model for the Neptune system, a model that seems to do a better job predicting the orbits of all those unruly and rambunctious Neptunian moons. While reading about this new model, I came across the following statement: “We also investigated sensitivity of the fit to Neptune’s Love number […].” And that gave me a delightful mental picture:

“Love numbers” are named after English mathematician Augustus Edward Hough Love. They’re also sometimes referred to as “Love and Shida numbers” to recognize the contribution of Japanese scientist T. Shida.

In the early 20th Century, Love introduced two ratios—traditionally represented by the variables h and k. h has to do with the elasticity (stretchiness) of a planetary body, and k is related to the redistribution of mass within a planetary body as it stretches. Shortly thereafter, Shida introduced a third ratio—represented by the variable l—involving the horizontal displacement of a planetary crust.

Taken together, h, k, and l tell you how much a planet, moon, or other celestial body can flex due to tidal forces. As explained in this paper on Earth’s Love numbers:

If the Earth would be a completely rigid body, [its Love numbers] would be equal to zero, and there would be no tidal deformation of the surface.

But of course Earth is not a completely rigid body. Tidal forces caused by the Sun and Moon cause Earth to flex “up to tens of centimeters,” according to that same paper. Tens of centimeters doesn’t sound like much, but as we all know, it’s enough to keep the ocean tides going!

In conclusion, I guess you might say that what’s true for planets is also true for people. Being completely rigid produces Love numbers equal to zero. So be flexible. Allow yourself to stretch a little, and your Love numbers will go up.

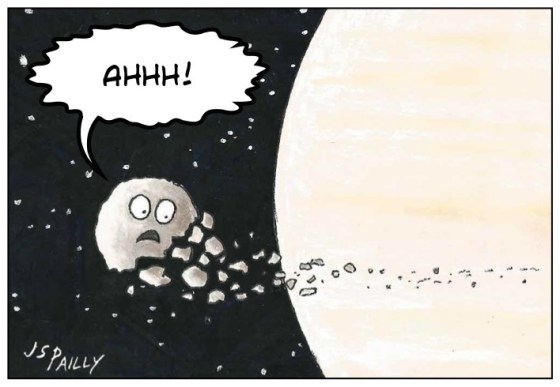

P.S.: Being flexible is healthy in any relationship, but at the same time don’t let others tug on you too hard. Know your limits—your Roche limit, I mean—because you don’t want to end up like this: