The spacesuits of today are cumbersome and uncomfortable. Worst of all, they’re not stylish. As a science fiction writer/illustrator, I want my characters to look good when they’re blasting through the vacuum of space, fighting bad guys and ridding the galaxy of evil. Fortunately, NASA researchers have provided me with a realistic (or at least plausible) excuse for dressing my characters the way I want.

It’s something I call the super sexy spacesuit, but the people who are actually developing the technology call it a mechanical counterpressure (M.C.P.) suit. Spacesuits today are basically body-shaped spaceships, and the whole interior needs to be pumped full of air to replicate atmospheric pressure. The big selling point for M.C.P. suits is that you wear them like regular clothing.

Almost. They’re a lot tighter than regular clothing. Not the way Spandex is tight. No, they’re way tighter than that. The fibers in the cloth are supposed to constrict on command, squeezing your body—squeezing so hard they end up exerting one atmosphere’s worth of pressure on your skin.

When you’re in space, you won’t notice that pressure. You’ve lived your whole life under one atmosphere’s worth of pressure, so you’re used to that. The suit should feel like a second skin, providing you all the comfort and flexibility of being naked (and perhaps the body image anxiety as well).

You’ll also be safer, at least in one sense, because minor damage to the suit wouldn’t cause catastrophic depressurization, the way it can with a contemporary spacesuit. However, there are still a few parts of the body where mechanical counterpressure won’t work so well. Fingers and toes, and all the small bones of the hands and feet, are really, really not meant to be compressed in this way. The same is true for your face and head, and mechanical counterpressure in the groin area could also be problematic.

But still, in the future some sort of M.C.P. spacesuit might be a plausible option, not just so we can survive in the vacuum of space but so we can look good doing it.

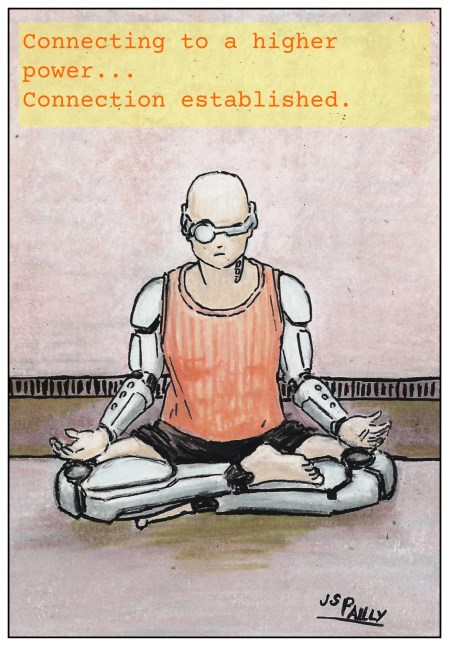

Or you could forego spacesuits all together and do this instead: