Sciency Words: (proper noun) a special series here on Planet Pailly focusing on the definitions and etymologies of science or science-related terms. Today’s Sciency Word is:

PLOONETS

If you’ve ever played Super Planet Crash (cool game, highly recommended, click here), then you know how difficult it is to maintain a stable orbit. The planets just keep pulling each other this way and that. It’s gravitational chaos! Fortunately, Super Planet Crasher doesn’t include moons. I imagine the game would be way harder if it did.

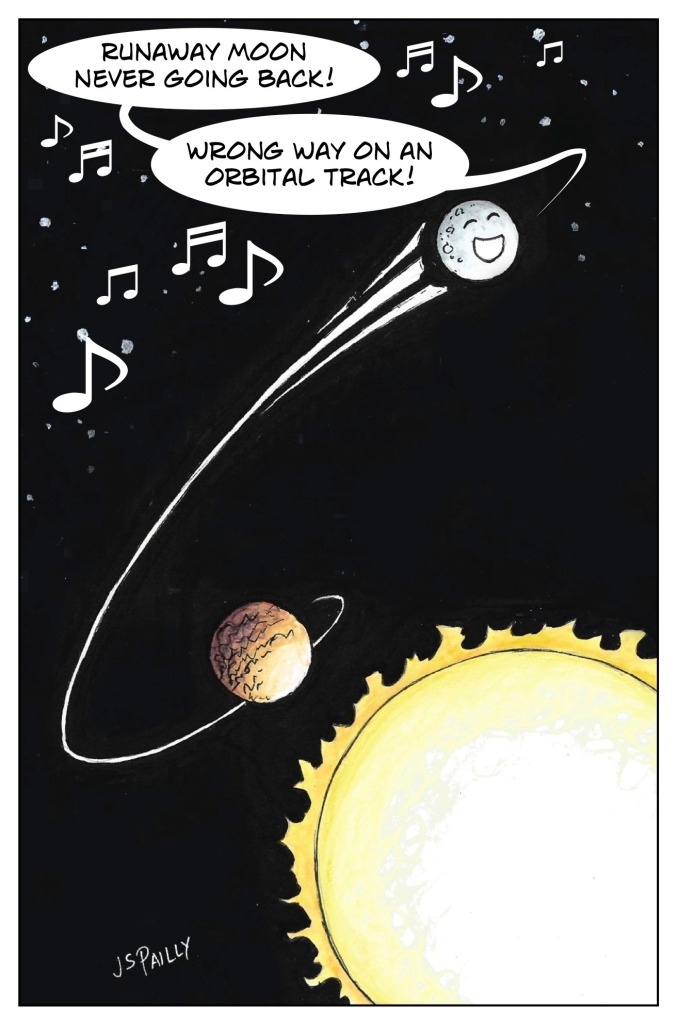

Recent research (click here) gives us a better idea of what happens to moons that get yanked out of their proper, moonly orbits. According to computer simulations, many destabilized moons will crash into their planets. A few will crash into the sun or be hurled out of the solar system entirely. But a surprisingly large number—almost half of them—will settle into new orbits around their suns, becoming planets in their own right.

The scientists behind this research have proposed a new term for these runaway moons. They want to call them “ploonets.” And furthermore, they describe four different kinds of ploonet we might find out there.

- Outer ploonet: a ploonet orbiting beyond the orbit of its original planet.

- Inner ploonet: a ploonet orbiting inside the orbit of its original planet.

- Crossing ploonet: a ploonet that crossed the orbit of its original planet.

- Nearby ploonet: a ploonet that shares almost the same orbital path as its original planet.

We may even be able to confirm the existence of ploonets in the near future. All we have to do it look toward so-called “hot Juipters”—Jupiter-like planets that have migrated dangerously close to their suns. If those computer simulations are correct, hot Jupiters should have shed small, icy ploonets all over the place during their migratory journeys.

I think we can all agree ploonet is an adorable word, but is this actually a useful term for astronomers and astrophysicists? I’m not sure. I guess it depends. How important is it, do you think, to make a distinction between planets that were always planets and planets that used to be moons?

It might be productive as an add-on designation, but I’m leery of an urge to be exclusive about it. Our giants reportedly migrated around a lot in the early solar system. Can we be sure one or more of our rocky inner planets aren’t ploonets? What about small planets that get caught by a giant’s gravity and stabilize in orbit around them? Moonets?

LikeLiked by 5 people

Well, Neptune has Triton, which is probably a moonet. Or would it be a dwarf moonet since Triton would have been a dwarf planet first.

I was also wondering if any planets in our own Solar System might be examples of ploonets. Mars seems like the most likely candidate to me, since it has a rather eccentric orbit and since it apparently/possibly snagged two asteroids from the asteroid belt somehow. But if that were the case, I feel like it would be very, very, very hard for us to prove it scientifically.

In the case of hot Jupiters with icy planets orbiting nearby, I think it would be fairly obvious what happened. But in most other cases, I feel like it would be really, really hard to know for sure if a planet is also a ploonet.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Triton is often described as a weird outlier. It’s probably why some SF stories take it to be an alien imposter or something.

Maybe one way to get insight scientifically is to study the chemical makeup of the bodies. That’s how geologists came up with the Theia impact hypothesis for how the Earth and Moon formed. Although I’m not sure how that could work with a gas or ice giant; too many of the relevant chemicals might be too deep in the planet.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The ploonet paper talked a lot about chemistry as well. A spectroscopic analysis of a exoplanet’s atmosphere could tell us a lot about where that planet originally came from. I’m not sure if that would be definitive proof that a planet is a ploonet, but combined with other evidence, it could help make the case.

LikeLiked by 2 people

If arguing over whether a planet ever orbited another plant, don’t we risk diverting scant brains and computer power into endless modeling debates? Would that truly advance our understanding?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m always a little wary of papers that rely solely on computer models. But this paper at least offers a testable prediction: we should find small, icy planets orbiting near hot Jupiters. If observational evidence backs up that prediction (or refutes it) then I think that does advance our scientific knowledge.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had a statistics prof once who said, everyone loves computer models – they’re fun. No one likes validating computer models – that’s hard work

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow…. great post. There’s lots of times when we talk about things that were captured and became moons (like Triton, which you mentioned earlier), but not a lot of talk about moons that escaped. I never really thought about them before, so thanks for sending what’s left of my brain spinning! 🙂

Glad to see you back, too. Looks like the break helped.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! I didn’t like being away for a whole month, but I needed the time to really think about some things.

As for the ploonets, I never really thought about moons escaping their planets either. It makes sense, though. It must’ve happened somewhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can see why the term exists, it’s quite cute for astrophysics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, it’s definitely a cute term! And the authors of that paper put it to good use. But will other researchers start using the term as well? I don’t know. I sure hope so.

LikeLike

Well we have to find some first.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True!

LikeLiked by 1 person